I just got back from a road trip through the lands of the Oceti Sakowin. My traveling companions were my 29-yr old son and Nick Estes, in the sense that we had his 2019 book Our History is the Future: Standing Rock Versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance playing on the car stereo.

Our path was Mankato – Badlands – Wounded Knee – Pine Ridge – Black Hills – Homestake Mine – Bear Butte – Standing Rock. The book follows a similar path. Estes’ (Lower Brule) book begins with Standing Rock in 2016, but then goes back to the fight against colonization in the 1800s. He covers Minnesota 1860s, Wounded Knee 1890, the Missouri River dams in the 1950s, the Red Power movement and AIM in the 1970s, and a whole lotta stuff in between, linking Indigenous resistance in the past to Indigenous resistance in the present.

Here is a quote from one reviewer who synthesizes it pretty well: “Our History Is The Future traces not just an Indigenous politics of opposition, but a vibrant and omnipresent theory of decolonization that strives to create and preserve as well as resist … Perhaps the most powerful argument of the book is the conceptualization of Indigenous resistance as an omnipresent process that runs throughout the course of American history.” —Shelley Angelie Saggar, Hong Kong Review of Books

Looking down that dashed yellow line on a highway cutting across the Plains, we imagined the opportunities for #Landback as we crested each new vista.

This is Bear Butte, an isolated mountain just northeast of the Black Hills. Historically, the Oceti Sakowin would meet here to coordinate responses to settler colonialism. It’s well within the Great Sioux Nation as defined by the Treaty of 1868, but not within any of the current reservations.

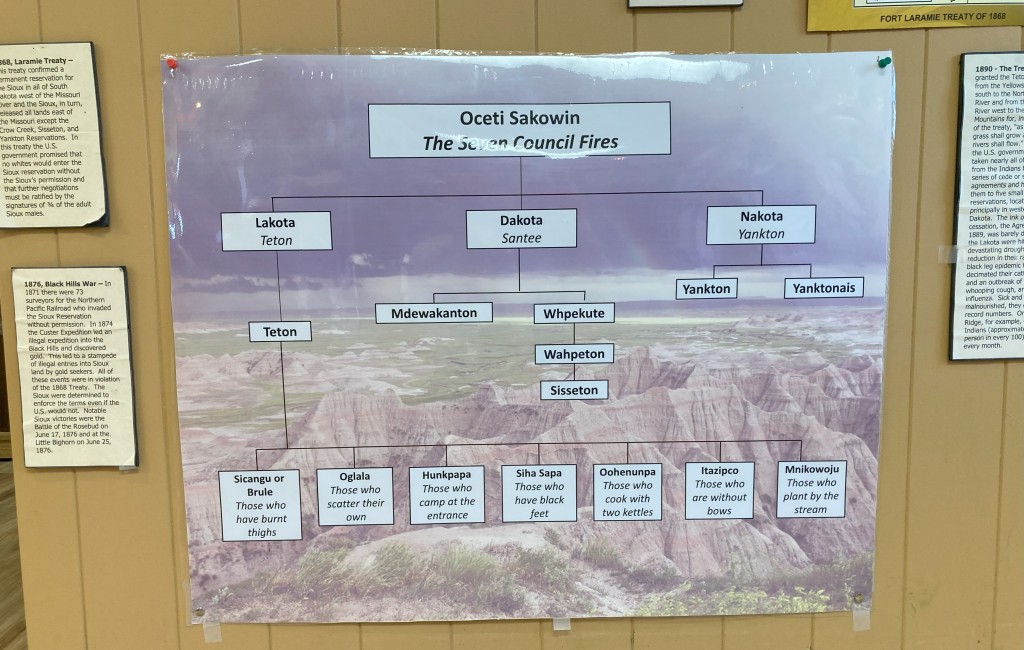

Some terminology which Estes covers in the book. This is from a poster at the Badlands National Park visitor center at White River. In true rez form, it’s just a trailer and easy to pass by, but whole new world awaits if you enter. It was immediately clear that most of the interpretive materials were written or curated by the tribe. Lakota/Dakota means “friends” or “allies.” The Oceti Sakowin are the Seven Council Fires, which have evolved and expanded over time.

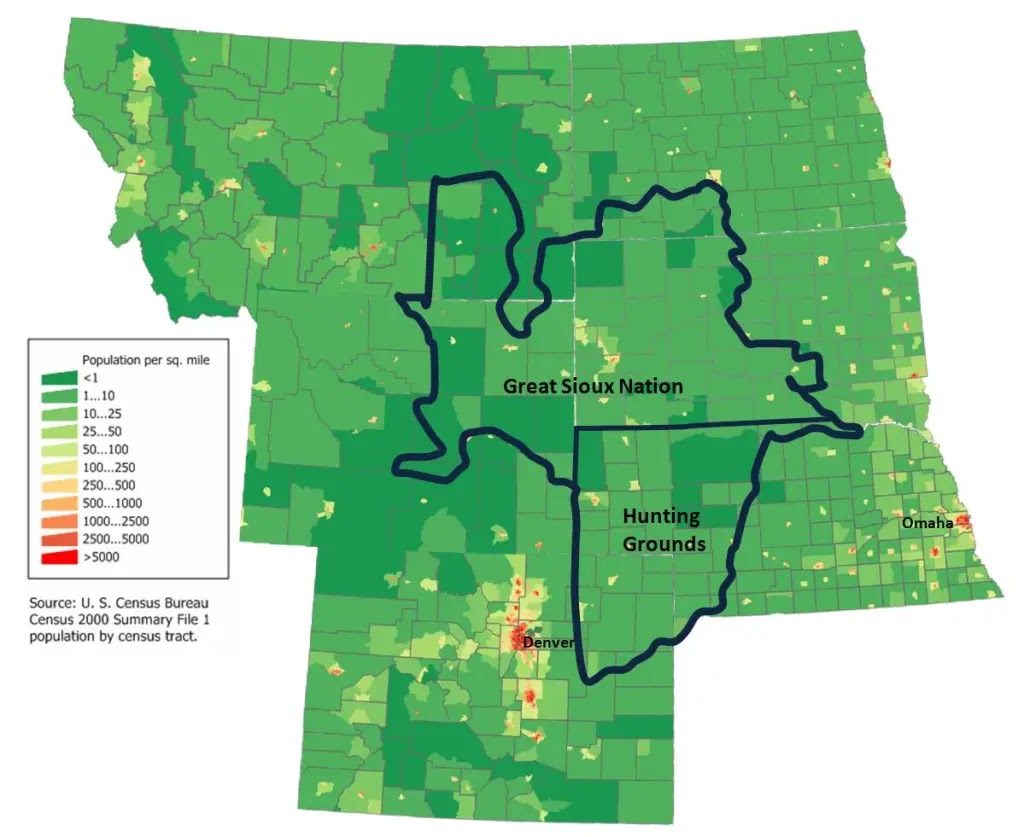

The Great Sioux Nation as described in the Treaty of 1868, after they successfully resisted the US in Red Cloud’s War. In 1980, in United States v Sioux Nation of Indians (more on that later), the Supreme Court affirmed the treaty, acknowledging that it represents “the only instance in the history of the United States where the government has gone to war and afterwards negotiated a peace conceding everything demanded by the enemy and exacting nothing in return.”

A lot of shit went down in the 1870s. The US Army sent Custer -illegally- into the Black Hills to confirm reports of gold. He did. The Lakota call it the Thieves’ Road. Settlers poured in and President Grant contrived a war to “open the land.”

White society celebrates this today. Custer did a lot of things, but his work to steal the Black Hills is honored above all else. There is Custer County, Custer town, Custer School, Custer State Park – even Custer Chiropractic.

Homestake Mine is one of the main reasons for the genocide. Eventually, they tunneled 8000’ deep and became the world’s largest gold producer. It opened in 1876, the same year as Grant’s contrived war to steal the Black Hills. The next year, while the landowners (the Lakota) were being hunted down and herded into prison camps, the mine was sold for $70,000 to the Hearst family and their partners. Two years later, it was listed on the New York Stock Exchange. Eventually, they dug a hole 8,000 feet deep and became the world’s largest gold producer for many decades. Royalties for the Lakota? That would be a zero.

The open pit can be seen from outer space.

You can even drink lattes next to a playground next to the mine pit, normalizing the associated land theft and suffering.

The entire era of ethnic cleansing is celebrated via pioneer nostalgia, much of it displayed along the highways.

Should you pull over for a cup of coffee, even then the celebration of ethnic cleansing and genocide is impossible to avoid.

The official narratives are absurd— carefully curated for white sensibilities, with ethnic cleansing dismissed as some inevitable event, like the changing seasons. Here the genocidal violence is called “the passing of their lands to the whites.” The land itself is largely empty, overrun with invasive weeds, and devoid of buffalo except at national parks and Native reservations.

This sign could easily be converted from distance to time. Here’s what I imagine:

Wind Cave – time immemorial; Custer 1874; Mt Rushmore 1927.

By 1888, when this pic was taken, most of the Lakota had been in concentration camps (“reservations”) for 13 years, and their kids deported to re-education camps (“boarding schools”).

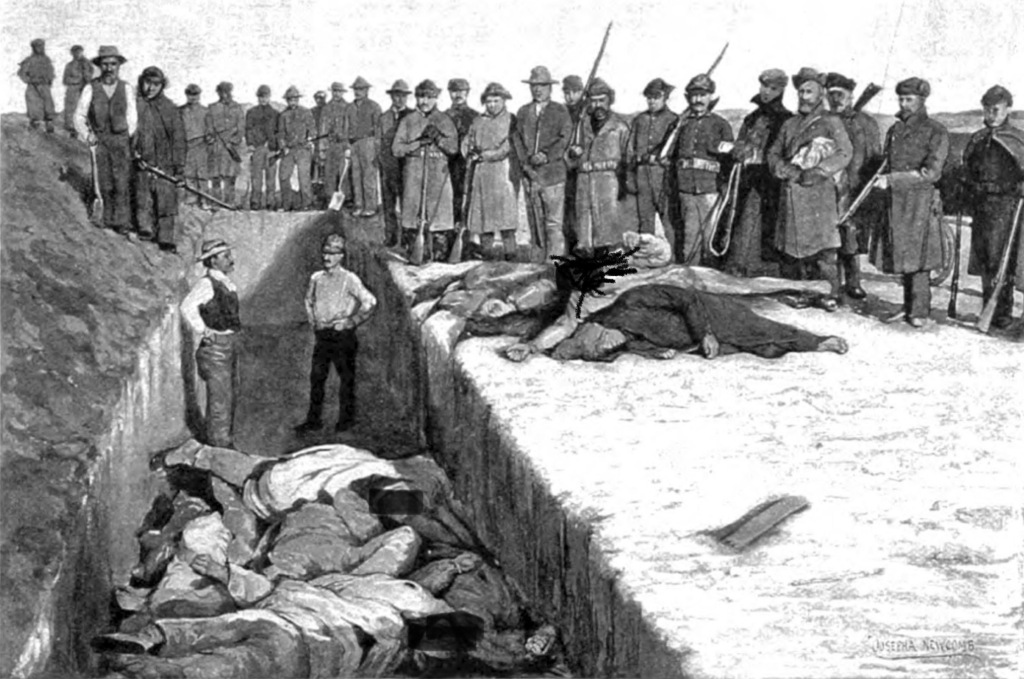

In 1890, Natives across Turtle Island sought hope in the Ghost Dance. White people freaked out, and the 7th Cavalry sought revenge for Custer’s defeat— so they massacred 300 unarmed civilians at Wounded Knee. One thing I never appreciated until now, until driving across South Dakota, is how far Spotted Elk’s group traveled and how close they were to their final destination when the massacre happened. They were traveling from Cherry Creek at Cheyenne River Reservation to Pine Ridge, where they figured they would be safe. That’s about 120 miles. They made it 116 miles before Col. Forsyth had them stopped, disarmed, and slaughtered.

The US army buried many in a mass grave.

My pic from the same spot.

Here is Spotted Elk (#63) (whom they called “Big Foot”), who had been in DC two years earlier. He was very sick from pneumonia at the time. Forsyth knew this – even visited him in his tipi and offered him a heated tent – the day before the massacre.

Wounded Knee is still an active cemetery for descendants’ families today. Buddy Lamont, killed by the US during the 1973 occupation, is remembered there with one of the more prominent memorials.

Also honored there are those killed by the GOONs in the early 70s.

In 1927, this KKK white supremacist desecrated the Six Grandfathers. White society honors him for it. White settlers call it the ‘Shrine of Democracy,’ though it adds insult to injury on stolen land. Our hiking around Black Elk Peak was regularly interrupted by helicopter tours taking people to see the carved mountain.

The backside shitasses of Indian killer presidents. Actually, this is about four miles away, but perhaps they had big asses. George Washington wanted the American Revolution to acquire Native lands (see Ned Blackhawk’s new book, The Rediscovery of America). He also razed Iroquois towns and crops, which is why they call him ‘Town Destroyer’ to this day. Thomas Jefferson wanted to ethnically cleanse all lands east of the Mississippi, mostly by driving Indians into debt and forcing them to sell their land — kind of like the World Bank way before its time. Theodore Roosevelt was openly racist against Natives. And every Native knows that Lincoln oversaw the Mankato executions and the expulsion of the Dakota from Minnesota.

Today, most of western South Dakota is private ranches – no buffalo, some cattle – granted to whites via the Homestead Act, propped up with federally-subsidized water and ag programs, all to support anti-government conservatives. Go figure. Buffalo restoration is constrained by cattle interests. I’ve got a whole blog post on the history of the buffalo, from their evolution with Native peoples to the present.

Sitting Bull’s image is fading here. It’s up to our generation and our children to keep his memory alive. I was just re-reading some of his quotes in Dee Brown’s Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. It’d been decades since I’ve looked at that book; there’s some damn good stuff in there.

Standing Rock was gorgeous, still green from late spring rains. Opportunities to restore the land and bring back the pte oyate (buffalo) abound. Standing Rock has a growing herd.

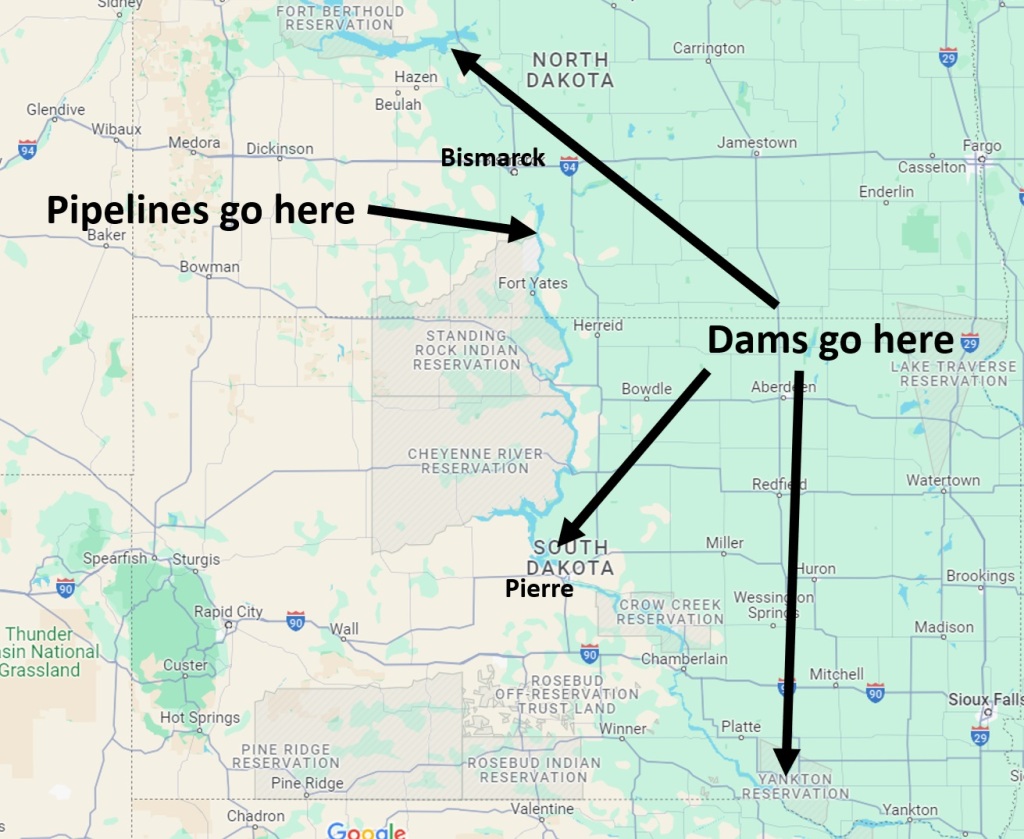

It was amazing how much the land changes once you cross the Missouri. Here’s where Estes’ book really hits it out of the park. His chapter 4 goes into great detail about this. Nearly every reservation on the Missouri River was flooded by Army Corp dams in the 1950s, destroying their towns, most of their homes, and their best land, and forcing them onto the uplands. White towns were avoided and spared.

The provocatively-named Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) followed the same practice, rerouting from Bismarck to Standing Rock without so much as a public meeting; it was all behind the scenes. #WhitePrivilege. Maybe it should be called the White Special Access Pipeline. This pic is from where it crosses hwy 1806 just a couple miles upstream of Standing Rock.

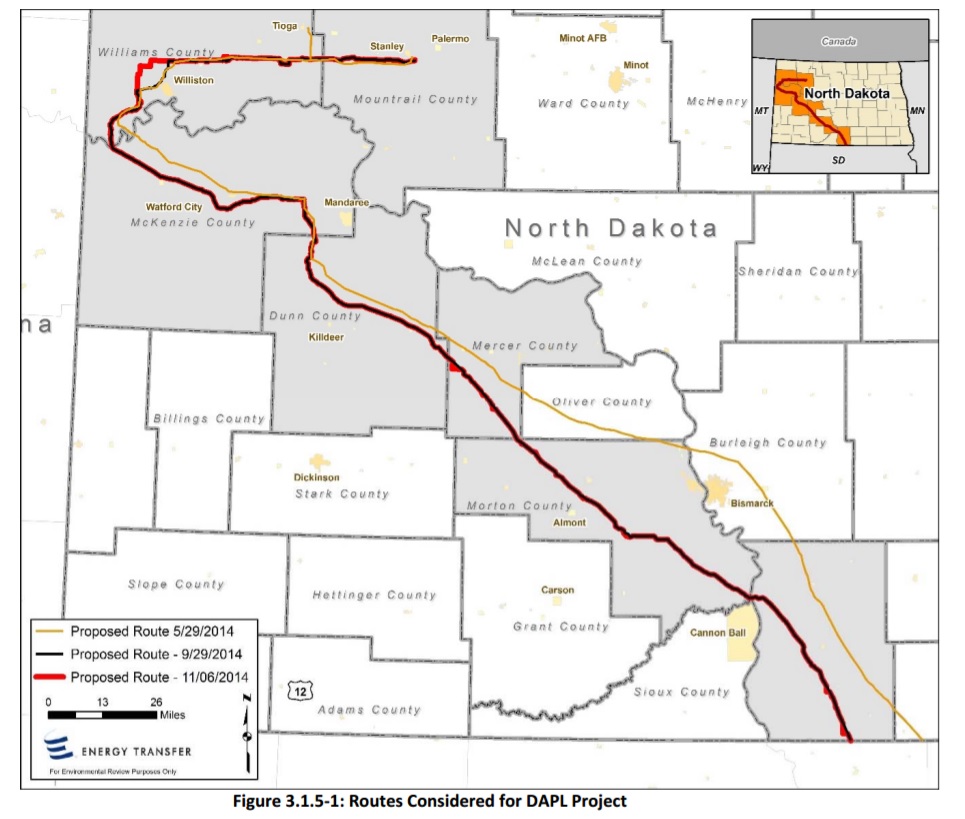

This map, from page 22 of Energy Transfer Partner’s application for a route permit from North Dakota, shows the initial pipeline corridor north of Bismarck, as well as the lack of changes after they met with the tribe in 2014.

Estes’ book is clear – dams are built just downstream of reservations and flood them; pipelines go just upstream and threaten them. For white towns, the opposite policy is used.

The site of the Oceti Sakowin camp of #NoDAPL water protectors in 2016. Turtle Hill is back left. In the Lakota language, rivers are animate objects. Mni waconi, water is life, because water is alive and gives life to us.

The bridge where state, county, and city police from white suburbia across the nation tested their military surplus weapons on peaceful protestors, injuring many. I’ve got a blog post about that: Red pilgrimage: right-wing counties send their cops to Standing Rock.

The area where the police urinated on the sacred items of the Treaty Camp.

The bridge over the Cannonball River today is peaceful, and we saw many species of birds here – orioles, flycatchers, vireos, towhees, dickcissels, swallows, grosbeaks, and four eagles.

Per an east coast judge, DAPL operates today without a final permit. #WhitePrivilege. The Final EIS will be released in late 2024. Shutting it down remains at option. I suspect Biden wouldn’t act on that until after the election. Meanwhile, a refinery in ND is no longer taking Bakken crude; it’s using soybeans to make renewable diesel.

Across the lands of the Oceti Sakowin, Native buffalo herds continue to grow. Estes’ book is, ultimately, a hopeful call to action.