Port Townsend is S’Klallam (or Klallam) land. The town occupies the northeast corner of the Olympic Peninsula, where the Straight of Juan de Fuca meets Puget Sound. The tides, as well as every bird, fish, or orca traveling into or out of Puget Sound, has to pass Port Townsend. The land looks and feels a bit like coastal Alaska, swathed in Sitka spruce and other evergreens, with the jagged purple and white peaks of the Olympics and Cascades showcased between tall firs at every view. But it’s also a part of the Lower 48, a place where the wild meets the urban, where north meets south, where fireweed and California poppies overlap.

The S’Klallam (which means “strong people”) lived here and they still do. They never saw a white man until 1787, when a stream of British, American, and Spanish fur traders began arriving in vessels thru the Straight of Juan de Fuca.

Five years before they ever saw a white man, in 1782, S’Klallam and all the indigenous peoples from Mexico to Alaska saw up to a third of their people die in a smallpox epidemic. The epidemic originated in Boston in 1775.

The Europeans advanced slowly at first. Hudson’s Bay Company operated in the area, and the S’Klallam traded furs at Fort Langley (near Vancouver, BC) (established 1827), Fort Nisqually (1833), and Fort Victoria (1843).

In 1842, mass migration along the Oregon Trail began. American settlers began to increase exponentially. All of Washington west of the Columbia River was disputed territory between Britain and the US until 1846, when the US/Canada border was finalized.

In 1850, the Donation Land Claim Act offered parcels of Native land to white Americans, a kind of affirmative action socialist program for whites only. White immigration surged and the first homesteads were established at Port Townsend the following year. It was the first permanent European settlement on the Olympic Peninsula. The number of white settlers in Puget Sound swelled to 4,000. Two years later, the US created Washington Territory.

By 1855, the Natives of Washington were outnumbered and under pressure to sign away their land. On January 26, at Point No Point, the S’Klallam signed away 438,000 acres in exchange for less than 4,000 acres near Port Gamble. The deal included $60,000 to be spread out in annuities. The Chemakum and Skokomish were also part of the Treaty of Point No Point.

During the treaty negotiations, most leaders refused to sign. Chief Chetzemoka (číčməhán), a S’Klallam leader from qatáy (Port Townsend), convinced the other leaders to sign. The promise of fishing and hunting rights at “usual and accustomed” places was the centerpiece of his argument.

For those who moved to Port Gamble, life was difficult for the next hundred years. They were denied most of their treaty rights and even forced to move again. The annuities were slow to arrive, and the fishing rights were denied them until pretty much the 1980s, after the Boldt Decision.

All the while, the S’Klallam persisted. In 1874, a contingent from Dungeness, who had never removed to Port Gamble, pooled their savings and bought land at the base of Sequim Bay, now called Jamestown. Because they did this on their own, outside of a treaty, this group was not federally-recognized until 1981, after decades of battles in court. Another group near the Elwha River Delta gained official recognition in 1968. The damming of the Elwha River in 1913 was devastating to them, destroying the salmon run and submerging their sacred “creation site”. The removal of the Elwha Dam in 2011 was a landmark event in the tribe’s history.

Today, the S’Klallam are split into four parts: three in the US, each federally recognized as a separate entity, and one in Canada.

- Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe

- Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe

- Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe

- Scia’new First Nation (or Becher Bay Indian Band), near Victoria, BC, includes some S’Klallam as well as members from at least three other ethnic groups.

Today the S’Klallam tribes all self-govern, providing a variety of social and cultural services for their citizens, as well as the Jamestown Family Health Clinic in Sequim, which provides healthcare for both tribal members and the general public. They also engage in habitat restoration and manage fisheries jointly with the state of Washington.

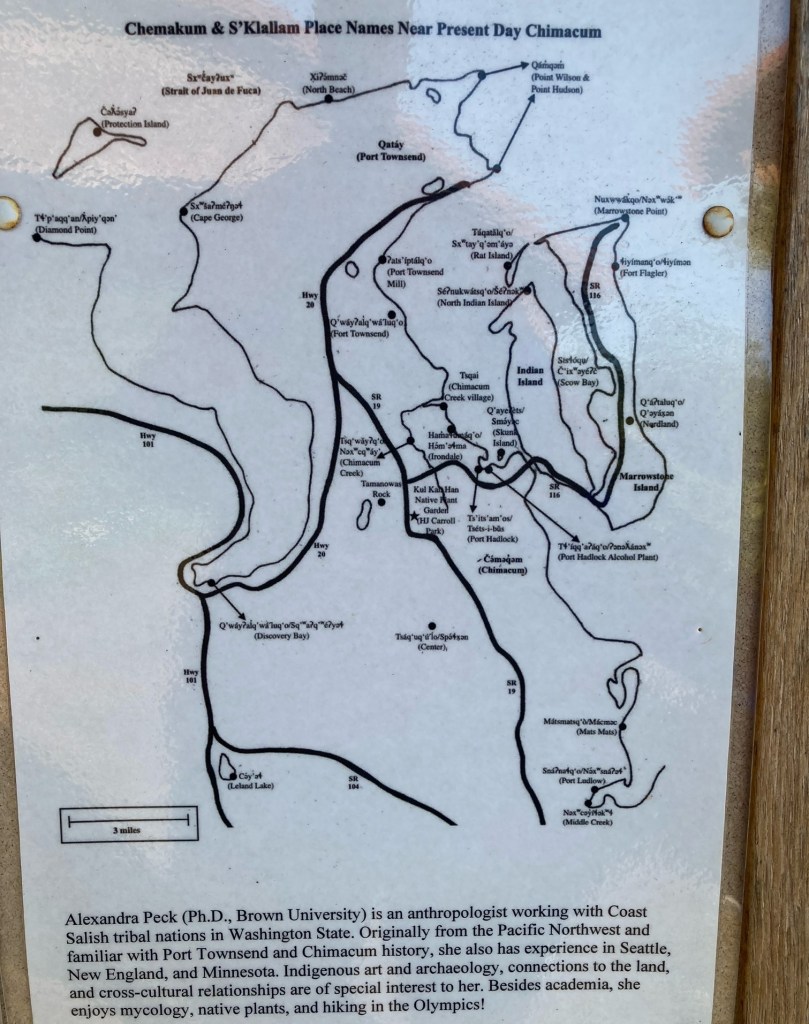

The area was also used by a number of other Coast Salish people, most notably the Chemakum, relatives of the Quileute on the outer coast. Here I post, in three separate photos, a sign from HJ Carroll Park in Chimacum, which provides some of their history. Click on each to enlarge.

For a reverse land acknowledgment of Port Townsend, examining who and what is currently honored, who Townsend was, and Rainier, and Wilson and others, see this post.

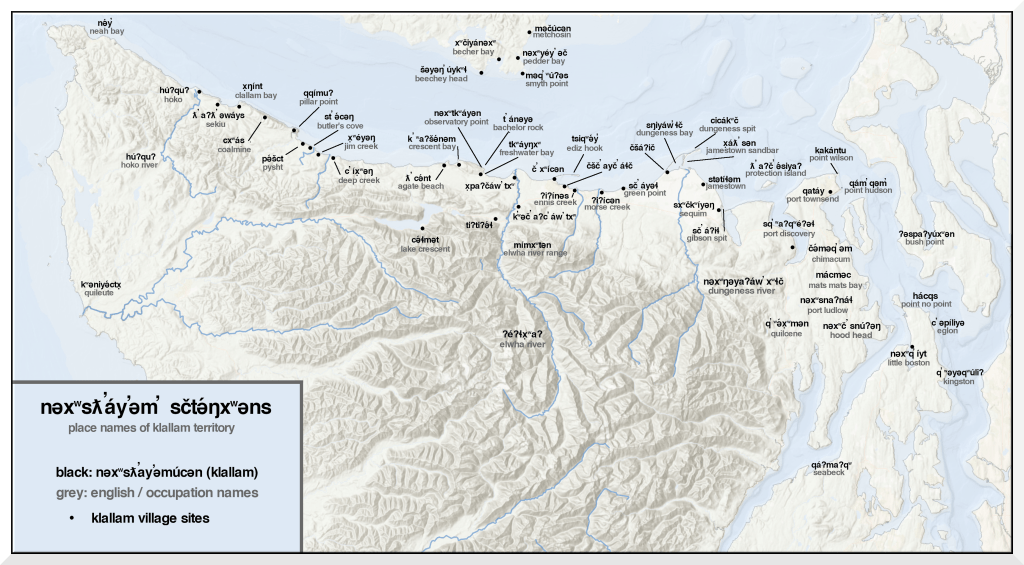

Adding this link with Native place names of the region: https://decolonialatlas.wordpress.com/2021/01/29/place-names-of-klallam-territory/

Thank you for this beginning to remember. So important.