Women have always occupied positions of strength and respect across Native America.

For starters, most tribes were matrilineal. This generally meant that when a couple marries, the husband moved into the woman’s town and joined her family. Her brothers, the uncles, oversaw her household and important issues regarding her children; her husband was merely a guest. This afforded women a great degree of protection against abusive men, who could be quickly run out of town by relatives.

This happened, starkly, in several cases involving European fur traders married to Native women. In 1712, an English fur trader among the Yamasee warned his buddies because, in Yamasee society, “the women Rules the Rostt and weres the brichess.”

Political power

The power of women extended deep into the political arena, especially in eastern North America. The Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy, going back five-hundred years, had a gender-based system of checks and balances: only men could hold office, but only women chose them. The men in power, especially the war chiefs, could be removed from office at any time.

The women’s standards for male political leaders remain high, as described here in the Iroquois Constitution. “Their hearts shall be full of peace and good will and their minds filled with a yearning for the welfare of the people of the Confederacy. With endless patience they shall carry out their duty and their firmness shall be tempered with a tenderness for their people. Neither anger nor fury shall find lodgement in their minds and all their words and actions shall be marked by calm deliberation.”

In the 1600s, Puritan women, consigned to a status akin to indentured servitude, were aware of the powerful political status of their Indigenous counterparts. When Cherokee leader Attakullakulla met with an English negotiating party in 1765, various clan mothers and matriarchs were with him. The English men came alone. Attakullakulla, immediately dubious of their intent to negotiate seriously, asked them, “Where are your women?”

Related to this is the traditional power of judgement and clemency that women had regarding prisoners. It was the women who decided which captives should be killed, traded, or adopted into their homes. In some cases, it was the women, aggrieved and furious over the killing of their children, who tortured captives.

It was women who granted clemency, as in the fictional story regarding Pocahontas asking her father to spare John Smith. (That didn’t really happen. Pocahontas was about ten years old at the time. Smith was spared for strategic reasons and was made to promise fealty to Powhatan.) The story probably emanated from a well-documented case in Florida in 1529, when the wife and daughter of Chief Harriga of the Tocobaga pardoned Juan Ortiz, a Spanish captive. In fact, they rescued him from a torturous death several times and eventually helped him escape.

My grandmothers

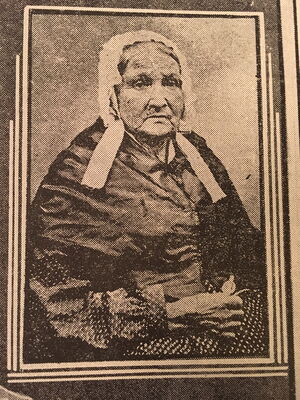

One of my many-great-grandmothers, Nan-Ye-Hi “Nancy” Ward, Beloved Woman of the Cherokee, is well-known for both her military feats and diplomatic efforts. You can read all about her online – at Wikipedia and at her WikiTree bio page.

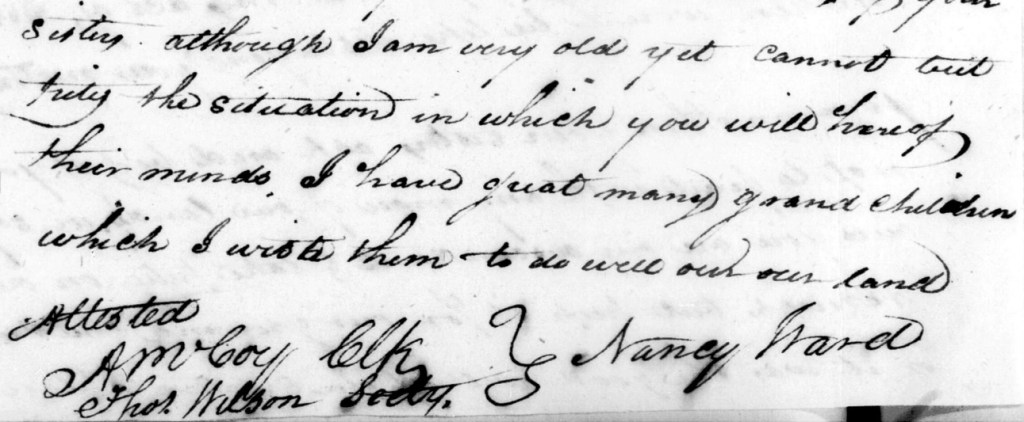

Late in her life she passed on her legacy to her daughter, Ka-ti Kingfisher, granddaughter, Jennie Walker, and great-granddaughter, Susannah Fox Taylor. All four of them were among the thirteen women who signed a petition in 1817 to the Cherokee National Council, asking them to not give up any more land to the white men. The council they wrote to included at least one of Nancy Ward’s grandsons (Major John Walker). Years later, John Walker’s son, Jack Walker, would be assassinated after a Council meeting for advocating giving up all lands and moving to Oklahoma.

In the petition, Nancy wrote, “We have raised all of you…. We have understood some of our children wish to go over the Mississippi but this act of our children would be like destroying your mothers. Your mothers, your sisters ask and beg of you not to part with any more of our lands….”

Susannah, Nancy Ward’s great-granddaughter, was only nineteen at the time of this petition. It wasn’t her first letter to be preserved in history. At age twelve she was a student of the Rev. Gideon Blackburn’s missionary school. Desperate for funding, Blackburn wrote a plea for support to President Thomas Jefferson. He included, as Attachment A, a letter from Susannah. Here is a transcription of it.

The Cherokee leaders ignored the women’s petition and signed what became Cessions 23 thru 26 in 1819. It was a slippery slope. By the 1830s, the State of Georgia allowed white pioneers to rob and rape with impunity. They also allocated Cherokee parcels to whites by lottery, so the pioneers were very targeted in their attacks. In 1834, Jennie, now 62, decided to flee to Indian Territory (Oklahoma). Those were difficult years, with the tribe split on whether to stay or go. If they made it to Indian Territory, there were no homes or services waiting for them. Jennie died within a year.

The Trail of Tears

At the time of the Trail of Tears, Susannah was 40 years old with 12 kids, ages 2 to 23, living in what is now Bradley County, Tennessee. On May 26, 1838, Cherokees woke up to troops of the US Army, commanded by General Winfield Scott, entering their cabins and farms. They were rounded up and forced into stockades. By nightfall, white pioneers were stealing their clothing, furniture, and livestock, and moving into their homes. Most of my family members probably ended up at Camp Foster or Camp Worth, at Rattlesnake Springs, just north of present-day Cleveland, Tennessee. According the Wikipedia, “a historical marker once stood near the site.” I guess no more. That’s why these stories must be retold. Hundreds died in those camps before the march west even started.

So many people died at the beginning of the Trail of Tears that the Cherokee Nation argued for permission from the US Army to manage, under contract, our own ethnic cleansing. Of Susannah’s 12 children, four went. Thomas Jefferson (“Jeff”) Parks and Richard Taylor Parks, ages 17 and 15, helped their uncle Richard Fox Taylor in driving wagons. Their older sister, Almira, and older brother George Washington, joined, probably to keep an eye on them. Uncle Richard was in charge of the 11th Detachment, leading over a thousand Cherokees from their homeland to Indian Territory during the winter of 1838-39. In 1814, he was one of hundreds of Cherokees who fought with Andrew Jackson, saving his life.

Meanwhile, Susannah stayed behind. She could do that because her husband, Samuel Parks, was a white man. Samuel nevertheless contracted to provide transport services. (His contract dispute with Cherokee Chief John Ross eventually went to the US Supreme Court – see Parks v Ross, 52 US 362, 1850.)

Going forward

Of Susannah’s 12 children, seven eventually ended up in Indian Territory, three managed to stay back with her in Tennessee, one died of cholera in Nebraska on his way to the California Gold Rush, and one died in Idaho (I have no idea why).

Both of the boys driving the wagons, Jeff and Richard, returned to Tennessee after the trip, but then Jeff went back and settled near his sister in the Goingsnake District (Delaware County today). He married Maria Ann (“Ann”) Thompson, whose family had gone to Indian Territory a year before the Trail of Tears, when Ann was seven.

Thomas and Ann settled near what is now Jay, Oklahoma. Their first child, Susan Parks, was born in 1848. She is my great grandmother, the mother of my grandma Fannie Carr. In her older years, she lived with Fannie and was thus that grandma who lived with my father when he was a child. When I was child in California, my grandma Fannie lived with us for a while. When my dad was seven, his father died suddenly of a heart attack, leaving Fannie to raise six boys during the Great Depression in one of the poorest counties in the nation.

These are my grandmothers – warriors, fighters, survivors.