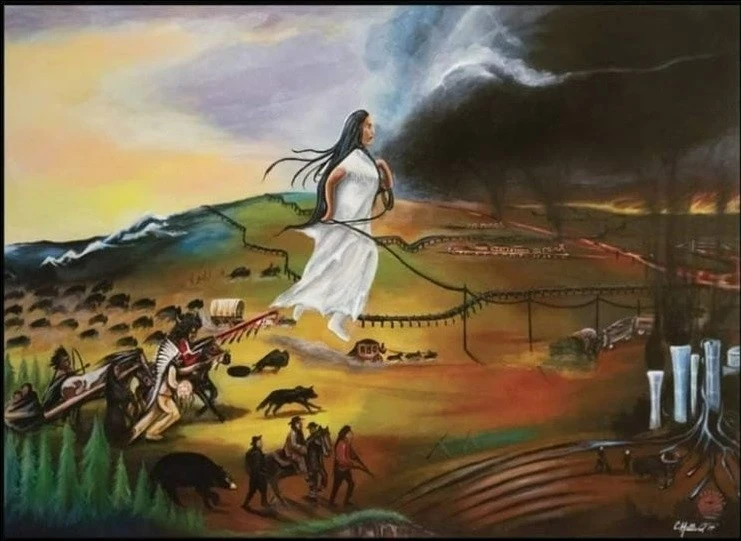

Rather than emanating from the brains of highly-evolved European men, it was actually Native American ideas regarding equality, personal liberty, and leadership accountability that fueled Europe’s Age of Enlightenment, ultimately leading to the American and French Revolutions, as well as modern concepts of human rights and equality.

These are the basic concepts presented in the opening chapters of The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity by David Graeber and David Wengrow. They go on.

In the 1600s and 1700s, Europe had no democracies. What they had was massive income inequality coupled with massive oppression of the poor by the rich. People were born into status; it was a caste system. Across the pond, the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy had a thriving republic, and women had powerful political rights across much of Native America. No one was born into status. Because leadership had to be earned, it was a land of great orators who maintained positions of leadership by giving away food and gifts to those in need.

Native American ideals shocked European colonizers, from Jesuit priests to the kings’ men, and made their way back to Europe in the stories they told. There, these radical notions of individual freedoms became a sensation – and ultimately, they revolutionized Europe and colonial America (literally).

Conservative forces, such as noblemen and kings, countered, attacking the source. The Indians in America only embrace these notions, they said, because they are simple savages, at an early stage of human development, uncivilized. Those talking points, in turn, became the mantra of the colonizers and the basic historical big picture we all grew up with.

I’ve read a lot of history books – European-centered, Indigenous, original source material, etc. – yet nothing prepared me this mind-blowing concept. The myth of Western Civilization, that every progressive idea came from Europe, that indigenous cultures around the world are quaint windows into a primitive past, is shattered.

Some of the professional reviews on Amazon are eye-popping. One compares it not with Charles Mann’s 1491 or Harari’s Sapiens, but with the works of Galileo and Darwin. A history professor at UCLA writes, “Graeber and Wengrow have effectively overturned everything I ever thought about the history of the world…. The most profound and exciting book I’ve read in thirty years.”

Regarding what they call the Indigenous Critique, I’d seen the trees, just not the forest. I’m familiar with many of the stories, and even some of the exact quotes, they use to build their case.

The Benjamin Franklin quote I saw coming as they built up to it. This is one of Dawn’s first examples that Native societies were making an impression on the Europeans.

“When an Indian Child has been brought up among us, taught our language and habituated to our Customs, yet if he goes to see his relations and make one Indian Ramble with them, there is no perswading him ever to return, and that this is not natural merely as Indians, but as men, is plain from this, that when white persons of either sex have been taken prisoners young by the Indians, and lived a while among them, tho’ ransomed by their Friends, and treated with all imaginable tenderness to prevail with them to stay among the English, yet in a Short time they become disgusted with our manner of life, and the care and pains that are necessary to support it, and take the first good Opportunity of escaping again into the Woods, from whence there is no reclaiming them.” – Benjamin Franklin, 1753

I can think of another example not in Dawn.

“Thousands of Europeans are Indians, and we have no examples of even one of those Aborigines having from choice become Europeans!” – Hector de Crevecoeur, 1782

Dawn uses the famous Huron orator, Kondiaronk, as their primary example of the Indigenous Critique, criticizing everything from European manners and parenting methods and calling them out for their deception and religious hypocrisy. Because of money, Kondiaronk argues, they do little except out of greed. Those familiar with Native history can probably think of many examples of this critique, coming from Tecumseh, Red Cloud, Chief Joseph, and others.

One example that Dawn does not use (though, to be honest, I haven’t finished the tome yet) is this 1765 gem from Attakullakulla regarding women’s equality. In most tribes, especially in the East, women had special political powers, especially the right to depose male leaders if they acted recklessly or in bad faith. Thus, women needed to approve all treaties. When the Cherokee showed up to negotiate with the English, and saw only English men there, Attakullakulla was dubious they were sincere. His first question: “Where are your women?” Even Puritan women, who lived in near-servitude, were aware of the rights and authority of Indigenous women.

Dawn then goes on to describe how accounts of these stories went viral in Europe, so much so that the Jesuit Relations, a 64-volume set of missionary diaries from North America, were blamed for contributing to civil unrest and the French Revolution.

The American colonists were equally inspired to apply Native concepts of individual freedom in their fight for independence from the King of England. Many of them dressed as Indians during the Boston Tea Party to make a statement – that they, like the Natives, can reject authorities they don’t like. (I’m not sure if Dawn includes this example either.)

But once the American colonists gained that independence, they quickly adopted the conservative counter-argument – that the Natives believed all that stuff about freedom and equality and respect because they were simple savages. Essentially, when the Declaration of Independence states “all men are created equal,” it’s adopting an Indigenous concept. Yet, it goes on to mention “merciless Indian savages.” By the 1800s, any credit to the Natives is long forgotten. Here is Thomas Jefferson in 1824:

“Let a philosophic observer commence a journey from the savages of the Rocky Mountains, eastwardly towards our seacoast. These he would observe in the earliest stage of association living under no law but that of nature, subsisting and covering themselves with the flesh and skins of wild beasts. He would next find those on our frontiers in the pastoral state, raising domestic animals to supply the defects of hunting. Then succeed our own semi-barbarous citizens, the pioneers of the advance of civilization, and so in his progress he would meet the gradual shades of improving man until he would reach his, as yet, most improved state in our seaport towns. This, in fact, is equivalent to a survey, in time, of the progress of man from the infancy of creation to the present day.” – Thomas Jefferson, 1824

I haven’t encountered this yet in Dawn either, but I’m pretty sure it’s coming.

If you don’t want to read the entire 700-page book, and have trouble just obtaining the first few chapters about the Indigenous Critique, one can find shorter versions in some essays and reviews on line:

- A summary of Kondiaronk’s arguments.

- Another summary of the Indigenous Critique.

- Graeber and Wengrow write a short paper using 1500s Mexico to illustrate similar points.

In 2020 (actually before Dawn was published), Bridget Orr, an English professor at Vanderbilt, picked up the baton in a paper that added examples of French and English plays from the 1730s that also used Native American foils to challenge oppressive European culture, especially with respect to women. Later, Irish playwrights used similar examples, from the “black legend” of Spanish conquest in Latin America, to challenge English oppression of Ireland.

Quite a fascinating read. The review was sufficient for me to go purchase. There is so much that the world is begining to reevaluate as it becomes a smaller place. Thank you for sharing Stephen.

nice

I’ve added a bit more nuance to this at my Substack at this post: https://substack.com/home/post/p-159066657

I recently read Kathleen Duval’s “Native Nations.” Chapter 2 is entitled, “The ‘Fall’ of Cities and the Rise of a More Egalitarian Order.” I talks about what we went thru 900 years ago with the rise and fall of Cahokia and similar urban centers. She provides a tangible example of the Indigenous Critique, back when we had to critique ourselves. Like “Dawn of Everything,” she paints a world that has gone thru urbanization and authoritarianism as more civilized than those still saddled by it.

Duval writes, “By the 17th and 18th centuries, most of Native North America looked nothing like the cities that Europeans came from, but that was not because they were primitive or never had cities. Instead… most Native Americans had rejected cities’ centralized power… prompting the development of some of the most egalitarian societies in the early modern world.”

She shows that the historical record is clear: authoritarian rule, building walls, coerced obedience, and extreme inequality mean the society is entering the rinse cycle. It’s still a rather uncivil place as far as “civilization” is concerned.

Natives went thru that. Colonizers brought it back. The arc of settler colonialism bends toward tyranny, but tyranny can fall hard, paving the way for an alternative future built around sustainable smaller communities.

——–

There is also a new book related to human “civilizations” and decentralized economies. “Goliath’s Curse” by Luke Kemp reviews the rise and collapse of supposedly-advanced civilizations (which he terms Goliaths) over the last 5,000 years. Like Duval (my comment below), Kemp’s analysis includes the Aztec Empire and Cahokia – and the present moment.

He posits that most humans are kind and want to get along, but the powerful rise like organized crime syndicates to accrue wealth and resources, creating massive inequality, which precedes their collapse. After collapse, the masses are often BETTER off, reverting to the decentralized democratic communities like the kind found across much of Native America in the 1700s.

Because the modern situation is global, not regional, with more weapons and technology, and with climate change well underway, humans face greater peril than ever from the Goliaths. See this review of “Goliath’s Curse” here: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2025/aug/02/self-termination-history-and-future-of-societal-collapse