Full disclosure – I am working on a book. It covers Native history and how it is told today.

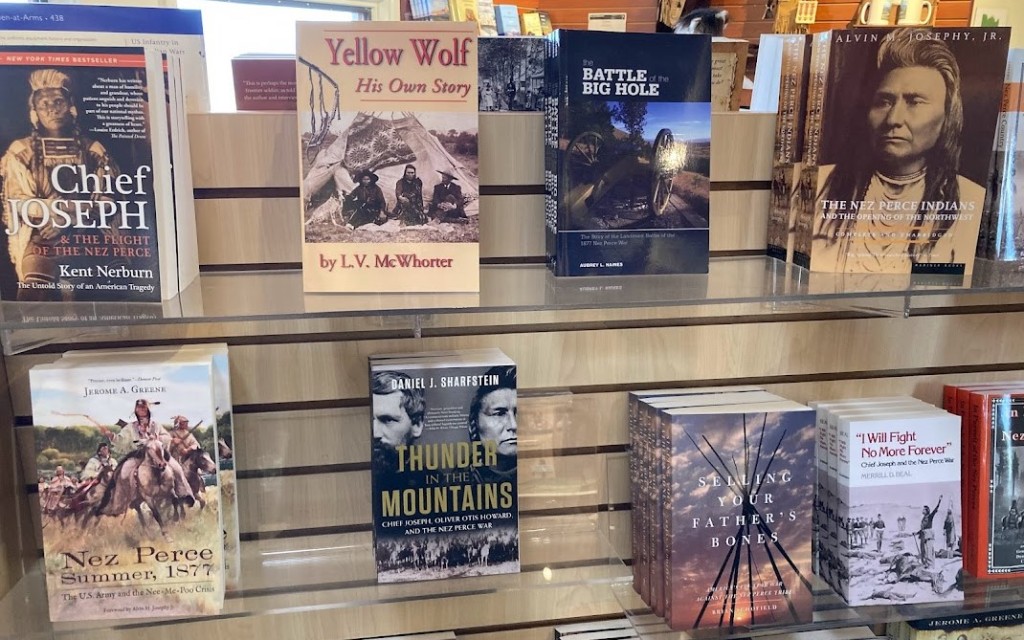

We can put books about Native history into four categories:

1) older books written by white historians, where Natives are “Indians” portrayed as wild or noble savages (e.g. most books before the 2000s);

2) older books that are actual Native accounts, either first-hand or second-hand, based on interviews in the early 1900s (e.g. Black Elk Speaks, Plenty Coups, Yellow Wolf);

3) more recent books written by white historians, where Natives are more nuanced, more sympathetic, and less stereotyped (e.g. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, 1491, Killers of the Flower Moon, and books by Pekka Hämäläinen); and

4) more recent books written by Natives about Native history (e.g. books by Vine Deloria Jr., Walter Echo-Hawk, and, more recently, The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee by David Treuer, Project 562 by Matika Wilbur, and books by Nick Estes and Ned Blackhawk).

Perusing the book offerings at the Fort Phil Kearny visitor center museum gift shop, I saw the usual assortment. I struck up a conversation with the guy working there. He was white, though claimed to have a Lakota name which was bestowed upon him after he badgered an elder at Pine Ridge for a year and a half. Eye-roll. Whatever, Kenny Boy. To his credit, he seemed to have read most of the books in the store. I laid out the four book types described above, and told him it was my impression that the last category – Native history written by Natives – seemed to be about one per cent of the total, or less. “That’s about right,” he said. In fact, I didn’t see any “category 4” books there.

My intent is to add to that last category.

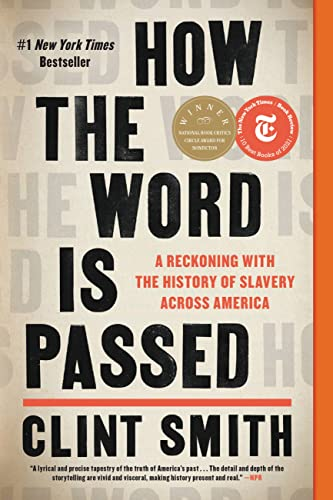

While my project is not just about the Indian Wars of the 1800s – there are hundreds, if not thousands, of such books – it will encompass them. To that end, I was in Montana and Wyoming to visit some historic sites – sacred sites, both marked and unmarked. As I traveled, I listened to Clint Smith read his book, How the Word is Passed. In a parallel effort to mine, he, a Black writer, visited several historic sites having to do with slavery, the Confederacy, and how those memories are told today.

Bitterroot Valley: Silence of the lands

If you’re not into these books, not a history buff, but just a passing motorist or a person living in the area, the world looks different. National monuments, historic sites, state parks, city parks, roadside historical markers, and even the names of towns, hotels, gas stations, and restaurants communicate the past. Not just communicate, they honor it. And that which they don’t communicate they do not honor; they are effectively erased from the public consciousness.

I began by following the flight of the Nez Perce from Lolo to Big Hole National Battlefield in western Montana. I expected to see a lot of signage along the lines of “Chief Joseph Trail” or “The Trail of the Nez Perce.” After all, when they fled their beloved Wallowa Valley in 1877, eight-hundred men, women, and children (three-quarters of them in those last two categories), the US media followed the story live – or as live as possible at the time. The people of New York and Philadelphia found themselves cheering on the bravery and resourcefulness of this community on the run, being pursued by several companies of the US Army. When they passed through the Bitterroot Valley, the white settlers boarded up their stores and grabbed their guns. But the Nez Perce passed peacefully, even stopping at their stores to purchase supplies for the road.

But now, in 2023, their story is difficult to find in the Bitterroot Valley. Instead, all the historical focus is on a different journey, when Lewis and Clark, coming from the other direction, traveled much of the same path in 1804. The highway was labeled the “Lewis and Clark Trail,” with a special icon of two intrepid men in silhouette. Quickie marts and grocery stores paid homage to them. Official historical markers were invariably about Lewis and Clark or other pioneer history.

Signs for Lewis and Clark outnumbered the Nez Perce saga about a hundred to one. Actually, a hundred to zero. There was one historical marker I pulled over to check out, but the actual marker was gone. There was nothing but a gorgeous green valley behind the post holes, backed by snowcapped purple mountains and a barn with a huge American flag on it. I marked the lat-long on my phone and later looked it up online. Yep, that was the only one that had mentioned the Nez Perce.

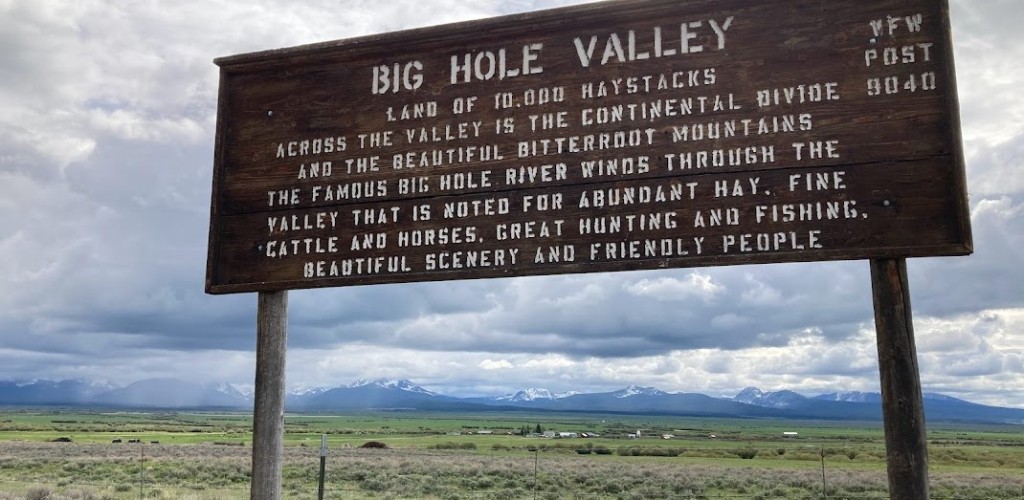

One sign in the Bitterroot Valley provided a list of Salish words for various locations, adding that “these ancient names testify to the sustainable tribal presence in this landscape reaching back thousands of years.” The same sign notes they are now gone, that “the tribe is now based at the Flathead Indian Reservation north of Missoula.” Near Big Hole, another sign proclaimed it the “Land of 10,000 haystacks… noted for abundant hay, fine cattle and horses, great hunting and fishing, beautiful scenery, and friendly people.” Nowhere was there any mention of how the valley went from the world of tribes to the world of friendly people. On that transition there was total silence, as if the Indigenous people had simply vanished in the wind, to be replaced by Pa Wilder building his little house on an empty prairie. All we can deduce is that, somehow, the Flatheads were replaced by friendly people with lots of cattle. This is what Clint Smith calls “white history.”

Big Hole: A small exception

At Big Hole National Battlefield, I was immersed in a more complete story. From the visitor center, I looked out over a lush high plain bordered by a sinuous willow-lined creek. In the displays in front of me, the Park Service and Nez Perce had collaborated on every word. In the distance, just to the right of the willows, a ghost village of tipi frames stood, a haunting memorial to the men, women, and children who were targeted while they slept – like a mass shooting, like the My Lai Massacre in Vietnam. The soldiers – some survivors from Custer’s Last Stand a year earlier, some volunteer militia (the “friendly people”) from the Bitterroot Valley who had just seen the peaceful Nez Perce families a few days earlier – were told to “aim low” as they trained their rifles on the tipis.

I walked out to the ghost tipis, grateful to be allowed on sacred ground. The sky was turning dark purple, threatening rain, but the grass was verdant, the camas were just starting to bloom, and the smell of fresh wet sage and the rattling call of sandhill cranes filled my senses. A small pamphlet was available as a walking guide to describe what happened there on the morning of August 9, 1877. It was graphic, sparing few details. Walking among the empty tipi frames was like visiting Auschwitz or a similar memorial.

Big Hole is not along a main highway. Tourists have to go out of their way to stop there. Apparently, few do. I was the only one there. In the neighboring towns, there is no mention of it. The ranger in the visitor center, a well-meaning white guy, said the Nez Perce descendants still come from Colville every year to remember.

Sacagawea: A good Indian

Sacagawea is mentioned in many of the Lewis and Clark memorials, though her story and her role is rarely detailed. She is what American white history has deemed a good Indian who, mostly unwittingly, furthered the project of ethnic cleansing, aka “manifest destiny.” There are more statues to Sacagawea than there are for any other woman in the US. Most gloss over her life. Like Pocahontas, she was kidnapped as a youth. Like Squanto, she successfully manipulated European colonizers into returning her to her homeland. Her lure was a win-win: guns for the Shoshone; horses and safe passage for Lewis and Clark.

The area of the joyous rendezvous with Cameahwait, her brother, in the valley between Dillon and Clark Canyon Reservoir, is unmarked. Yet, had this not happened, the Lewis and Clark Expedition may have ended there. They had already nearly reached the continental divide, the western edge of the Louisiana Purchase. To go further, they would be trespassing and land claimed by Britain, not to mention Nez Perce, Cayuse, Palouse, Umatilla, Yakama, etc.

At the lake, there are several markers, as well as a campground named after her brother Cameahwait. The Sacagawea Memorial, installed by the Montana Daughters of the American Revolution, says only that she provided “invaluable services.”

I was interested in how this resourceful, sex-trafficked, missing Indigenous girl found her way home, how she remembered the route she had last seen five years earlier, when she was twelve. As the expedition approached from the north, crossing an enormous broad valley, I saw they would have entered a short canyon between two cliffs. Ahead, on her right, she would have a seen a distinctive needle-like spire. Beyond that, the valley opens up again, sagebrush with willows lining the meandering Beaverhead River. And after that, a right turn at the next large meadow (now under the reservoir) and up over the pass to home. This she remembered. Based on Clark’s diary, she remembered details as far back as the Yellowstone River. As close as I could get to where I imagined this reunion occurred, I collected some sage, wet from a fresh rain, to celebrate the memory.

Greasy Grass/Little Bighorn/Custer’s Last Stand: Summer grasses

One of the most iconic sites in Native American history, it goes by three names and means different things to different people. Most Natives call it the Battle of the Greasy Grass, the Indigenous name for the river. The US government officially calls it the Battle of Little Bighorn, another reference to the river. It is a national monument, a higher honor than Big Hole, which is merely a national battlefield. Most people probably know it as Custer’s Last Stand. It lives as a distant reminder, like a passing shadow in the collective unconscious, that the land was not conceded without a fight. Yet, probably few people could tell you the historical context, the run-up to it, or what happened afterward. Most can barely mention the tribes involved.

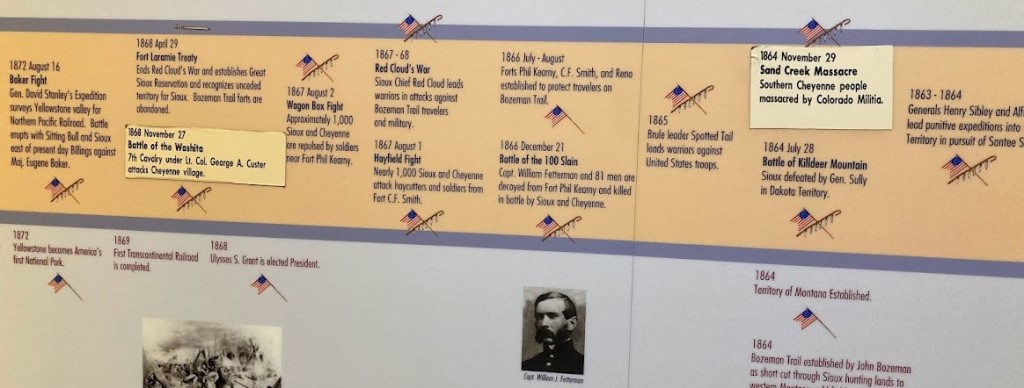

The battle itself stands out as anomalous in many ways. Yes, it was a deliberate attack by the US Army on an encampment that was predominantly women and children. That was nearly always the case, from the Pequot Massacre in 1637 to Big Hole in 1877 to Wounded Knee in 1890. Exceptionally, in this case, the attackers became the victims. It is difficult to think of another time that happened. Only the Battle of Mabila in 1540 or St. Clair’s Defeat in 1791 (which nearly wiped out the entire US Army at the time) compare.

The larger story around Greasy Grass is typical, and the massacre of Custer and his men did not change the final outcome. After trespassing minors (led by Custer) discovered gold in the Black Hills, the US contrived a war to take the land already agreed to be the Great Sioux Reservation by the Treaty of 1868. President Grant used the term “to open the land.” Custer’s Last Stand was one of several major battles in this war. Within two years of the massacre, the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho were subject to worse massacres, surrendered, and were rounded up and put in concentration camps that we still know today: Pine Ridge, Rosebud, Standing Rock, etc. In 1980, the Supreme Court ruled, yep, the war was illegally contrived and the tribes deserve compensation. But, rather than giving the Black Hills back, or any #landback, the Court awarded money. To this day, the tribes have refused to touch it. It sits in a special fund held by the Department of the Interior where it has grown to over a billion dollars. But, in one of the most principled stands of resistance anywhere in the world, the cash-strapped people of these reservations maintain that “the Black Hills are not for sale.”

None of this story is told to visitors at the national monument. Even the illegally concocted war is obfuscated so as not to offend white sensibilities, to avoid diminishing the sacrifices of the US servicemen. White history is easy to write, because the focus is about what not to write.

The vibe at the national monument is a lot like Arlington National Cemetery. As I park my car, I see rows and rows of white tombstones on the grass in front of me. More white tombstones are scattered around the hillsides, marking where each US soldier fell. A few mark where Natives fell, though not many fell here. Other signs describe the intensity of archeological investigation to understand what happened and who many have fallen where. All the focus is on honoring their bravery and sacrifice.

Standing on a hillside among the tombstones, I was immediately reminded of the famous Japanese haiku about imperialism:

Ah! Summer grasses!

All that remains

Of the soldiers’ dreams

I was disappointed that there is no access to the valley bottom, the running stream among the cottonwoods, where eight-thousand were camped, where, on a hot June morning in 1876, children played, older boys watched over the horse herd, the women gathered wild turnips, and the men slept in until someone yelled, “The chargers! The chargers are coming!” Walking among the cottonwoods down there would allow visitors to imagine the perspective of the Indigenous people, but that’s not the point of this monument.

It is not a place to point out that these were soldiers attacking mostly women and children. It is not a place to ask why Sand Creek, Wounded Knee, the Dull Knife “battlefield,” or countless other sites where Natives were massacred, have little to no memorial. None have the status or funding of Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument. Most actually have a barbed wire fence that says “no trespassing.” They are on privately-owned ranches, inaccessible to the public. Some of these ranches fly Confederate flags with AR-15’s emblazoned across them. Others allow limited visitation and coordinate with tribal descendants for ceremonies of remembrance. “We work with the tribes,” a friendly landowner at another site told me. “We’ve been here five generations.” I started doing math in my head.

The empty land

Leaving the Greasy Grass, I passed signs for Miles City and Sheridan. Further along various highways were towns named Custer and even Chivington, and counties named after Grant, Crook, and Sherman. Between the various Indian reservations, the Plains are a who’s who of Indian killers, making a modern map resemble a giant battlefield.

As I headed south toward the Powder River country, site of many battles, the land seemed empty. I felt as if I was a boat on a green sea. The Rocky Mountains do not gradually diminish and sink into the Great Plains. Rather, the plains rise up like a great green tidal surge, the lines of hills like swells in the ocean. At the western edge, the Bighorn Mountains emerge like a cresting wave approaching the shore, topped with whitecaps of snow. No towns, no people, no houses, a few cattle. The only buffalo I saw was on the Wyoming state flag. The land was ethnically cleansed, but for what? It appeared empty to me.

I suppose most of that land is privately-owned ranches, with leases for coal and natural gas. I saw some of the landowners, in cowboy hats, perched on barstools sipping coffee, watching Fox News to anesthetize themselves from the realities of climate change and the facts of history. Some of them, I suppose, were friendly people.

The erasure of the Nez Perce in the Bitterroot Valley, the glossing over of the contrived war against the Sioux and Cheyenne – with its connections to the Black Hills, the Homestake Gold Mine, and reservations such as Pine Ridge and Standing Rock – and the drastic differences in the memorialization of the lives lost at Little Bighorn as compared to those lost at Sand Creek or Wounded Knee, are not surprising to Natives; we are used to it. It parallels what Clint Smith found with respect to Black history. He describes a national commitment to “the country’s collective ahistoricism” to support white supremacy, the notion that this land is primarily for white people.

And yet, despite this repression of memory, the Indigenous people still remain, almost an underground society, but rising up like flowers on the Plains, supportive communities of compassion, committed to preserving the earth.

Very challenging project you’ve undertaken. Will be following your progress. Goo luck. 💪💪