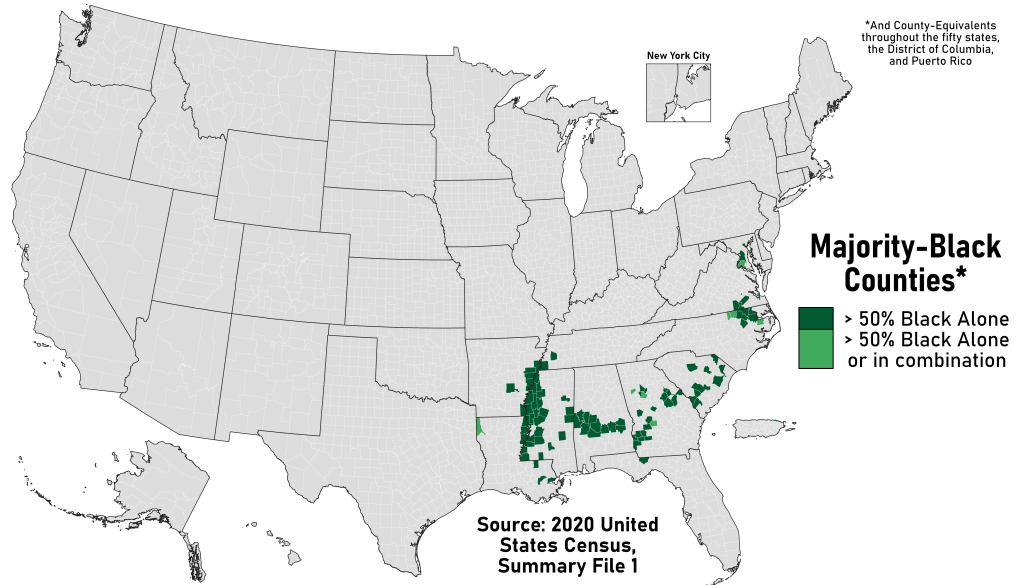

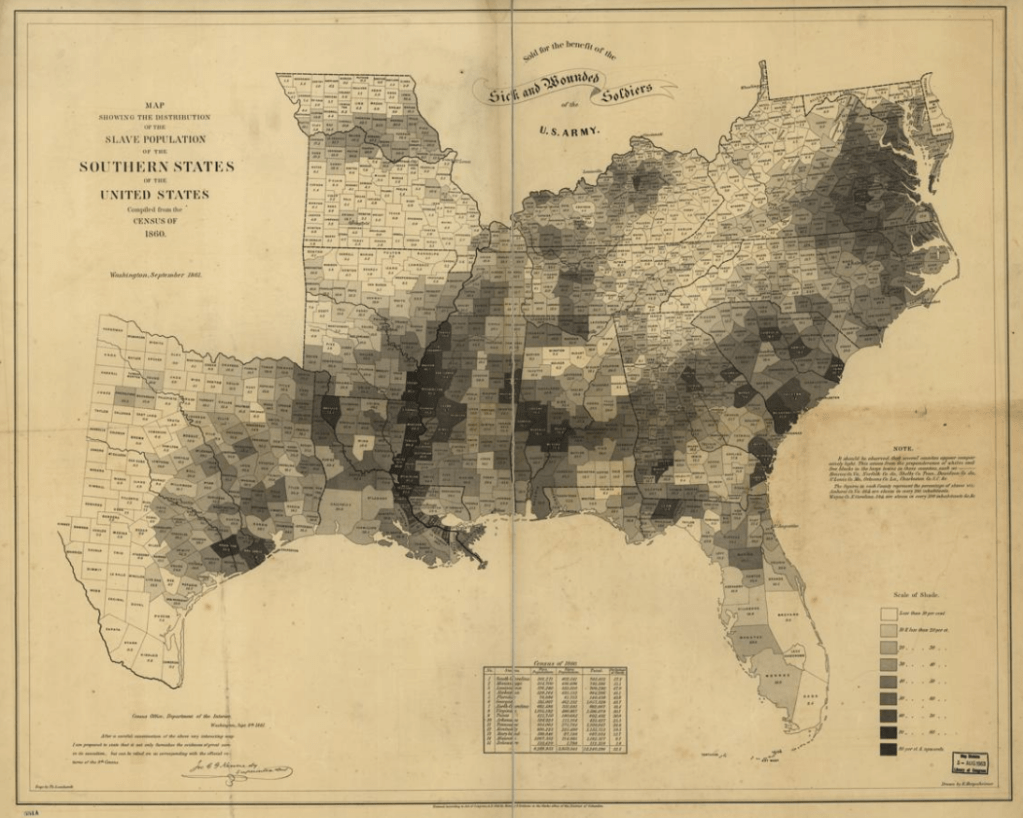

The 100-million-year story of the Black Belt, a crescent-shaped swath from Virginia to Louisiana, has been told many times – how a geological formation from the Cretaceous, visible today in the dark soils it created, can be seen in the patterns of human history, where Southern slave plantations were concentrated and where cotton was produced.

Today, that same crescent marks concentrations of Black people, voting patterns, and even where insurance companies rip people off. The term “Black Belt” reflects its diverse implications. It was first meant to describe the soil. As early as 1901, Booker T. Washington explained how it became used for a geopolitical region in which Blacks, first slave and now free, outnumber whites.

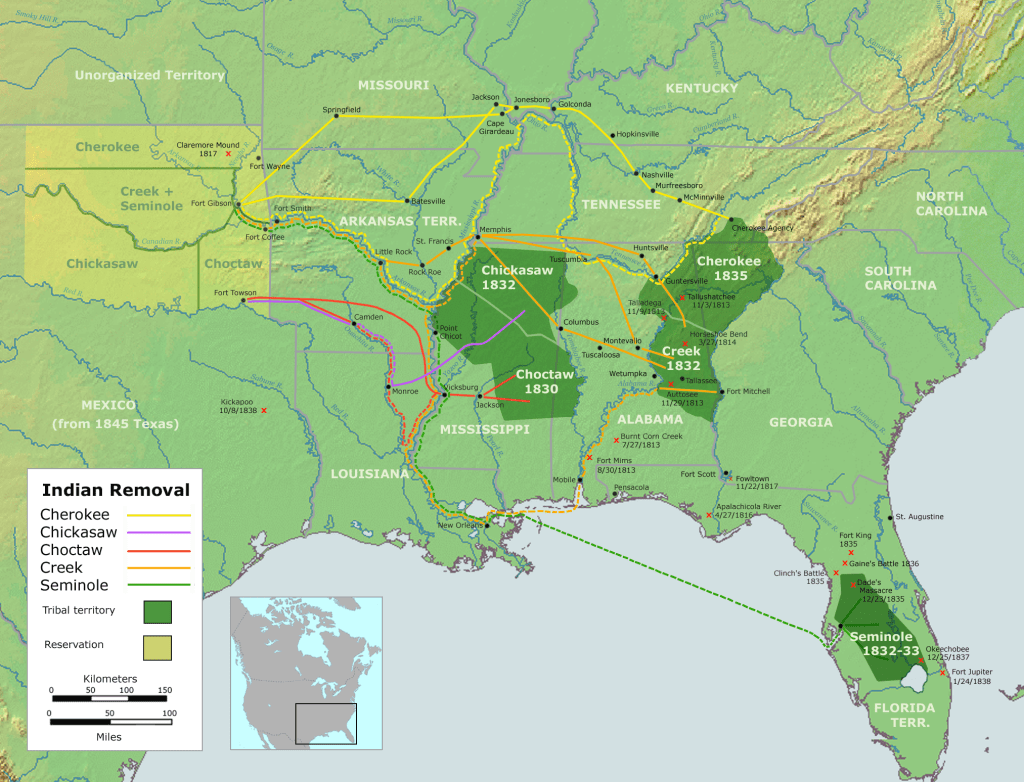

Missing from this story is the Native American piece. In her well-crafted and comprehensive book, By the Fire We Carry, Rebecca Nagle describes how the Indian Removal Act of 1830 – and the resulting ethnic cleansing called the Trail of Tears – cleared the path for all those rows of cotton and slave plantations.

Here are some poignant excerpts from her book:

“The Indian Removal Act passed the House of Representatives by a margin of only five votes. Most often the histories of Indigenous dispossession and enslavement in the United States are taught separately. But these two systems of oppression needed each other. What we think of as the Antebellum, or Deep South, was built on land Southern lawmakers fought for and won in the Indian Removal Act. And in 1830, the South had an additional 21 votes in the House, because enslaved people, who of course could not vote, were counted towards Southern states’ representation.”

“Expelling our tribes from our homeland was one of the largest and most expensive projects the young federal government had ever attempted. As historian Claudio Saunt has tabulated, the federal government spent, in today’s currency, $1 trillion – or $12.5 million per deportee – on removal. Some years, it was nearly half the entire federal budget…. Because land speculators acquired the land for almost nothing, the profits they reaped were unimaginable. The final wave of profiteers were the men who sat atop the slave economy. In the decade following the Indian Removal Act, over 300,000 enslaved people were moved from the Eastern Seaboard to the Deep South. For enslaved families, the Second Middle Passage broke apart an estimated one in five marriages and separated a third of children from their parents. With cheap land and free labor, the cotton economy boomed. By the close of the decade, cotton production in Mississippi increased ten-fold. And by the time of the Civil War, the Mississippi River Valley had more millionaires per capita than any other place in the US.”

Though I was taught some about slavery and a little about Indians in school, and though I learned later, as an adult, that the US was largely built with slave labor on stolen land, I never linked those two sins as tightly as Nagle weaves them. Of course, it makes sense — most of the Black Belt was Indian Country through 1830.

The Native story began, of course, tens of the thousands of years earlier, as Native peoples farmed the rich soils. The remarkable archeological site, Poverty Point, which dates from 2000 to 1000 BCE, lies at the intersection of the Black Belt and Mississippi River corridor. In the 1500s, DeSoto’s path of rape and pillage followed the Black Belt extensively. The historic walled city of Mabila, site of the epic battle between Tuscaloosa’s and DeSoto’s men, later became an area with the greatest density of slaves.

Here are some Black Belt maps that tell many stories.