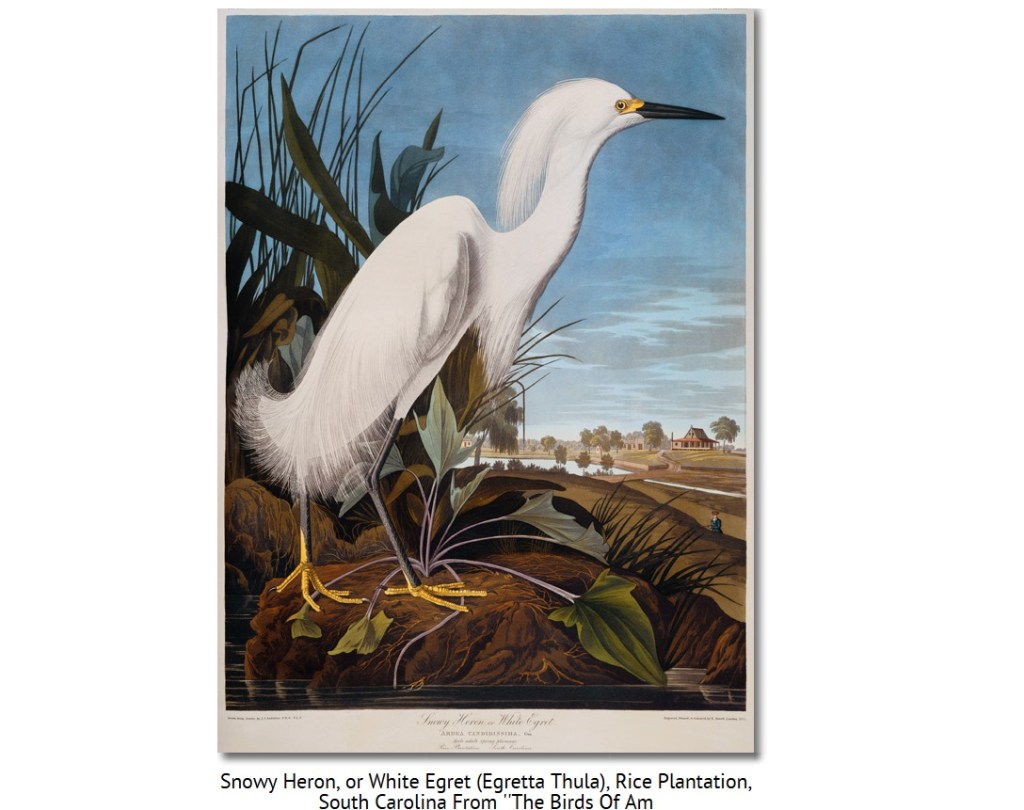

Nicolas Mirzoeff’s essay, The Whiteness of Birds, brought my attention to this painting.

There are layers here that probably tell us more about people than the about the ecology of the bird – about white history, white nature, white autonomy, even white ornithology – an invisible thread of slavery and ethnic cleansing.

The painting, of course, is by John James Audubon.

The bird is now known as the Snowy Egret. Its scientific name is still Egretta thula. “Thula” comes from the Araucano word for Black-necked Swan. It was applied to the egret in error, as happened with several Indigenous words for birds. It won’t be corrected – those are the rules.

In the background of Audubon’s painting is Rice Hope Plantation, near Moncks Corner, South Carolina. Audubon painted this in 1832, when enslaved people would have been working on 371 acres of rice and indigo under cultivation. They are not pictured. Not one.

Audubon is pictured, the small figure in the lower right, a white man with a gun.

Audubon would have been intimately familiar with slavery. He was born on a slave plantation in Haiti. As the owner’s son. By all accounts, he was surrounded by mixed-race siblings. His own mother was a French chambermaid, though she died shortly after his birth.

With a slave revolt brewing, his father took him and fled to France when he was just three. By the time Audubon was 19, in 1804, the Haitian Revolution was complete. For the only time in modern history – perhaps all history – a nation was created by a slave revolt. Audubon was then in the US. At that time there were only two independent nations in all of the Americas, and Audubon had lived in both. But the US did not recognize Haiti’s independence until after the Civil War.

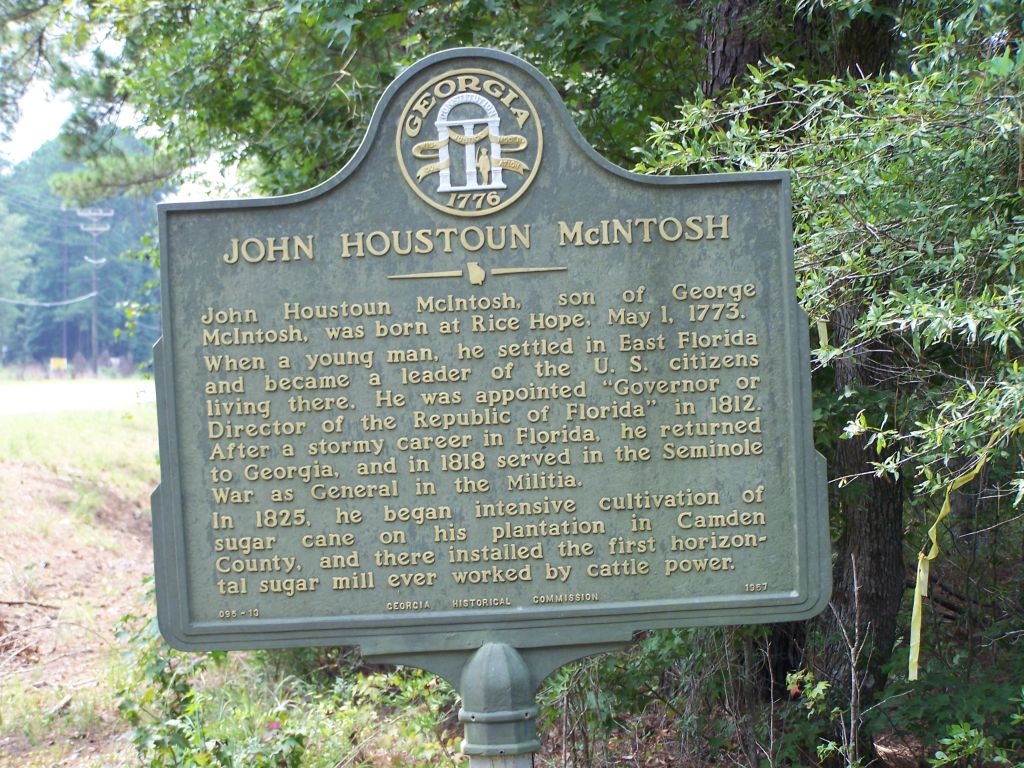

Twelve years before Audubon was born on a slave plantation, John Houstoun McIntosh was born at the Rice Hope Plantation. He grew up to serve as a general in the ethnic cleansing of the Seminole from Florida. The Seminole were not the first Natives to live in Florida. Originally, there were dozens of other tribes, mostly wiped out by English slavers in the early 1700s. There were sent up to Charleston and then off to plantations in the Caribbean. Enslaved Natives went out; enslaved Africans came in. When the Seminoles came in the early 1800s, they were refugees filling a vacuum. They were Red Stick Creeks (aka Mvskoke or Muscogee), allied with escaped Black slaves, fleeing Andrew Jackson.

In 1832, when Audubon painted the egret, the Indian Removal Act had just been passed. The US was allocating enormous resources to ethnically cleanse everything from Georgia to the Mississippi River. Lumber was being purchased, stockades were being built, wagons were being lined up. At the same time, other plans were under way. Money was invested, land was cleared, and slave quarters were constructed. By 1840, the Black Belt was opened to cotton farming and thousands of enslaved people were sold south from Virginia.

Today, Rice Hope Plantation is called Rice Hope Plantation Bed & Breakfast. According to a 5-star Yelp review, it has “tons of history.” Like the painting and the historical markers, there is no direct mention of slavery.

The existence of slavery has been so thoroughly erased that the name, Rice Hope Plantation, can now be used freely.

A few hours south, near Savannah, Georgia, there is a housing development called Rice Hope Plantation. According to their website, it is “a community jam-packed with resort style amenities such as a swimming pools, a lazy river, slide, splash pad, clubhouse with fitness center, lake for kayaking, playground and so much more.” It practically goes without saying, there is no mention of slavery.

Today, you can go online and buy prints of the painting for $500. The websites will tell you it is an Audubon print, it is a Snowy Egret, and Rice Hope Plantation is in the background. They may tell you that the print pairs nicely with his paintings of other herons. They will not mention the enslaved.

Pingback: The Whiteness of Audubon’s Snowy Egret | The Cottonwood Post

Thanks for writing this Steve and opening up people’s eyes to the erasure of Genocide