When addressing historic wrongs, and especially memorials that honor people that perpetrated historic wrongs, a common challenge is: Should we be holding these people accountable according to modern values and mores?

There are two big problems with this question.

- Almost always the wrong, let’s say slavery of Blacks and ethnic cleansing of Native Americans, was actually hotly debated and contested at the time.

- (and this is the key) Blacks and Native Americans have always been opposed to slavery and ethnic cleansing.

The question of “social mores” and society’s standards refers, implicitly, only to white society’s standards. By raising the question of whether or not (white) morals have changed, people of color are removed from the equation, shunted to the back of the room, and put in a position of debating the issue in a white-centric framework. It’s a fine introspective question for white society, but it erases people of color, both from the past and in the present.

Case study: Bird names for birds

By way of example, let’s look at the recent movement in the birding and ornithological community to rename birds that have been named after people. These honorific bird names are described as “verbal statues”, usually to white men in the mid-1800s. Some were slaveholders, others were Indian killers, and most were either associated with these men or comfortable naming birds – or rivers, mountains, forests, and towns – after them.

One example is a striking black and yellow oriole of the southwest deserts, known for singing its melodious song from the tallest yucca around. In 1837 in Mexico, ornithologist Charles Bonaparte first described the species for Euro-American scientists, giving it the Latin scientific name Icterus parisorum. The name honors the Paris brothers, businessmen who paid to transport specimens from Mexico to France. In 1854, Couch “re-discovered” it and named it after Winfield Scott, Commanding General of the US Army. Today it is known as Scott’s Oriole.

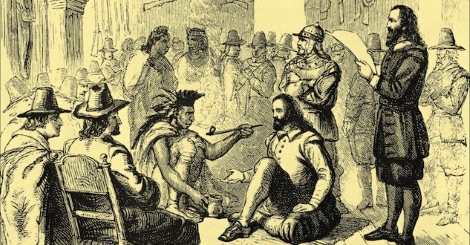

Scott, not a naturalist in any way, was honored precisely for his role in the US-Mexican War, which allowed the US to take over much of the oriole’s range. His resume also included his prosecution of the Black Hawk War and ethnic cleansing of Native Americans from the Midwest, and overseeing the arrest, detainment, and expulsion of the Cherokee during the Trail of Tears.

There are many more examples of honorific bird names memorializing those with checkered pasts. We can also examine the dismissive treatment of women in the few birds named after them, or the two species with Native names, albeit misplaced and over-written. More on that can be found here.

…and the American Ornithological Society

In 2020, in the racial reckoning in the aftermath of the George Floyd killing, the AOS’S North American Classification Committee (NACC), which is responsible for official bird names, modified their naming guidelines to be “responsive… to changing societal mores” (Winker). Under Part D, Special Considerations, they added, “The NACC recognizes that some eponyms refer to individuals or cultures who held beliefs or engaged in actions that would be considered offensive or unethical by present-day standards. These situations create a need for criteria to evaluate whether a long-established eponym is sufficiently harmful by association to warrant its change…. The NACC recognizes that many individuals for whom birds are named were products of their times and cultures, and that this creates a gradient of disconnection between their actions and beliefs and our present-day mores.” [italics added by me]

Thus, last year, they were willing to change McCown’s Longspur to Thick-billed Longspur. McCown had been a Confederate soldier. Others that participated in massacres or ethnic cleansing of Native Americans remain unaddressed at present. Like Scott’s Oriole, Abert’s Towhee, Clark’s Nutcracker, and others.

The entire argument, that social mores have changed, frames the issue from a Eurocentric position. To coin a phrase from Isabel Wilkerson in her book “Caste”, focusing on social mores, and by implication white social mores, is an example of white “expectation of centrality”, where the white historical perspective is the only one on the table. The AOS’s reasoning is also an exhibition of white fragility, a face-saving attempt to say that the land has shifted under them, and that in its beneficence they will consider new names. It was not that the AOS itself was in need of reform.

Society hasn’t changed

To be clear, not that much has changed. Then, as now, Blacks and Native Americans have always opposed slavery and ethnic cleansing. Within white society, both slavery and ethnic cleansing were hotly contested at the time. A war was fought over the former. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 and the resulting ethnic cleansings remain one of the most contentious and debated pieces of legislature in the history of the US Congress—and the Supreme Court. The removal of the Cherokee passed by a single vote after US Representative Davy Crockett (National Republican-TN) was voted out of office for defending Native rights. The streets of Washington DC were filled with polemical pamphlets, the social media of the day. Had the naming of Scott’s Oriole been fully vetted, it would surely have met white opposition.

The biggest change that has occurred is probably within the AOS’s membership, which now includes many more women and people of color than in the past. Their change in policy is welcome, and long overdue, but it is not due to tectonic social shifts underneath them; it is due to their membership becoming more diverse. The white story, and white history and white social mores, are no longer central.