In 1909 the University of Wisconsin lacrosse team adopted the first Native mascot. By the 1950s, they were commonplace. Beginning in 1968, Native Americans condemned the use of these mascots, arguing that they are based on stereotypes that “have a negative effect on contemporary Indian people… (and) block genuine understanding of contemporary Native people as fellow Americans,” to quote the US Commission on Civil Rights in 2001.

Many are surprised and confused that Natives object to Native sports mascots. After all, the Irish at Notre Dame embrace the Fighting Irish and the Lutherans at Pacific Lutheran are the Lutes. The key thing is this: those are mascots chosen by their own people groups. For most of the schools with Native mascots, Natives represent less than 2% of the student body. In nearly every case, the mascot was chosen by colonizing whites. What many of the papers presented here are suggesting is that these schools, by adopting Native mascots, are re-defining the collective white “we” to include Natives. Natives are part of “our” history. “We” were all part Native.

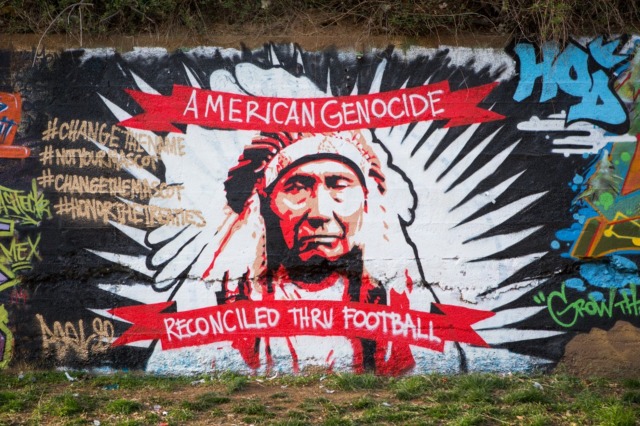

It sounds inclusive, but there are several problems with this re-defining of history. First, it absolves white society for genocide and ethnic cleansing. It “honors” noble savages, who like buffalo, had to be sacrificed to make way for modern white civilization; it was sad but inevitable. And now the issue is resolved.

Second, it is inherently in conflict with contemporary Native voices that object to it. Modern Natives, still in conflict with the larger white society, don’t fit in this story. It is not resolved.

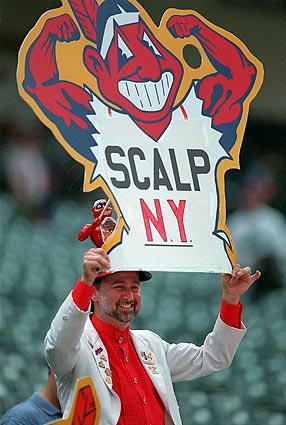

Third, the mascots are usually wrapped around violent and savage stereotypes.

And fourth, most of the time the teams get it all wrong, like when they use Sioux medicine man headdresses to represent ethnic groups from coast to coast.

The most prominent modern controversies have involved the Washington Redskins, Cleveland Indians, University of Illinois Fighting Illini, Florida State Seminoles, and University of North Dakota Fighting Sioux. The issue also affects thousands of professional teams and schools across the nation.

The arguments in defense of these mascots are fairly similar from case to case. See, for example, this editorial and associated on-line comments from Winters, California, regarding the logo for the Winters High School Warriors. These pro-mascot arguments don’t vary much from those used to defend the Washington Redskins or Cleveland Indians.

The main arguments by Native mascot defenders are:

- The mascot is not really causing any problem; there is no “problem” to be solved.

- It’s not meant to be racist; it’s about tradition and local pride.

- The mascot actually honors Native Americans.

- Among Natives, polls show the anti-mascot opinion is a small minority. Most Natives are not offended. Some Native Americans are fine with it. Indian activists that are anti-mascot are “out of the mainstream.”

- Few people care about this issue because the protests are small, so it’s not really a problem.

- Natives should spend their time focusing on real problems like poverty and alcoholism.

These are often accompanied by other belittling comments, such as: replacement mascots are “stupid,” this is “just another social tirade,” “fuck you,” and “it’s some sort of left-wing fake guilt trip.” That last comment is a bit prescient, hinting at the settler colonist power dynamic that underlies this issue.

Native leaders, writers, and activists are fairly unified in their opposition to these mascots. A quick review of indiancountrymedianetwork.com, nativenewsonline.net, or www.indianz.com will reveal scores of articles and editorials opposing the use of Native mascots. That said, there are a few exceptions. These usually occur when the mascot involves a specific local tribe and the school or university has consulted that local tribe and reached an agreement regarding usage protocol. The agreement between the Florida State Seminoles and the Seminole Tribe of Florida is one such example (although King

and Springwood 2000 argue this “agreement” is simply politically expedient and a product of the disproportionate power dynamic between the two parties). Another agreement, between the Rogue River School District and the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians, follows Oregon state law that requires schools to consult with local tribes regarding Native mascots. As part of the deal to retain their mascot, the school district is adding tribal history to fourth- and eighth-grade curriculums.

There is an extensive literature of academic investigations of Native mascots and their impact. A summary of most of the papers is provided here, in chronological order:

- Banks, D.J. 1993. Tribal names and mascots in sports. Journal of Sport and Social Issues 17(1): 5-8.

This article, by well-known American Indian Movement (AIM) activist Dennis Banks, provides a historical introduction to the topic, beginning with the respectful approach of the Stanford Indians in the early 1900s, the increase in racist fan behavior in the 1950s, and the beginning of Native protest in 1970, coupled with Stanford students dropping the Indian mascot in 1972.

- Davis, L.R. 1993. Protest against the use of Native American mascots: A challenge to traditional American identity. Journal of Sport and Social Issues 17(1): 9-22.

Based on interviews conducted during large protests against the Atlanta Braves and Washington Redskins during the 1992 World Series and 1993 Super Bowl, Davis describes Natives concerns centered on 1) aggressive “savage” behavior stereotypes, 2) a focus on the past that ignores Natives today, and 3) impacts on the mental health of children. Davis argues that the “vicious resistance” of mascot supporters is because they consider the anti-mascot position un-American and a threat to their “mythology of the American West,” where the genocide of Natives is dismissed and the establishment of “American civilization” is justified and glorified. Davis also argues that the rise in Native mascots in the 1920s, especially among men’s teams, is associated with White American male assertions of “hegemonic masculinity.”

- Slowikowski, S.S. 1993. Cultural performance and sport mascots. Journal of Sport and Social Issues 17(1): 23-33.

Slowikowski explores sport mascots through an anthropological lens, focusing on the rituals surrounding a sporting event and linking them to paleolithic hunting rituals of the past, where hunted animals were thanked and respected, providing good luck for the next hunt. That which was destroyed is now revered. From this perspective, Native mascots represent trophies of conquest, a nod to the “hunted,” and thus make the hunt (or the past) legitimate. This “imperialist nostalgia” uses mascots as a kind of “cultural souvenir.” As such, it is important that the mascots are seen as authentic—and not challenged by modern Natives.

- Wenner, L.A. 1993. The real red face of sports. Journal of Sport and Social Issues 17(1): 1-4.

This article introduces the other articles from this journal issue, discussing how White males have defined how history and cultural stories are told, and that now this is finally changing—through either business or altruistic motives.

This paper compares the use of Native and Confederate imagery at Florida State and Ole Miss, respectively. The authors describe an array of demeaning war-mongering and “savage” stereotypes associated with the Seminole mascot (e.g., an official booster club is called the Scalphunters), and explore its approval by one group of Seminoles, which they suggest is a matter of political expediency.

“When [FSU mascot Chief] Osceola leads the FSU football players onto the field, he signifies armed resistance, bravery, and savagery, and his appearance builds on the prevailing understandings of Indianness that construct Native Americans as aggressive, hostile, and even violent… It draws on the Euro-American knowledges of Native American cultures, misconceptions that paint them as savage warriors removed from the mores of civilization and eager for combat. To characterize the indigenous Seminole people or any other native nation of North America as warlike or bellicose dehumanizes and demonizes them. More important, it disregards both their cultures and their histories. It reduces them to a single aspect of life, namely, war, ignoring the numerous other experiences and activities more valued than war. Osceola, as portrayed at FSU, thus offers a stereotypical representation of Native American cultures and histories informed by racist notions and romantic sentiments.”

Next, they illustrate the stunning display of racial power at Ole Miss (complete with Confederate flags and students dressing as slave plantation owners) and the recent opposition to it, often led by a White football coach concerned for his Black players. The authors argue that “the nostalgic reincarnation of the Seminoles and the Confederacy not only fashion the self through mimicry (and mockery) of the other but they also restage racial hierarchies.” They describe the importance of these racialized symbols to neoconservatives, who defend the images with “denial, obfuscation, and even a refusal to acknowledge the racial components underlying these mascots.” The involvement of administrators and politicians (in mandating keeping racial mascots) suggests that “sports spectacles have become a fundamental node in the articulation of a defensive, reactionary rendering of Whiteness.”

- Black, J.E. 2002. The “Mascotting” of Native America: Construction, commodity, and assimilation. American Indian Quarterly 26(4): 605-622.

A Florida State (FSU) graduate explores the use of mascots to control Native Americans “by constructing Indigenous peoples as generic [e.g. all tribes are the same]” and “reducing them to appropriated commodities” via the branding and marketing of items for sale (e.g. Chief Illiniwek toilet paper at the university book store) and materials designed to promote university identity with the “tribe.” Focusing on FSU and the University of Illinois, Black argues that turning Natives into “souvenirs” allows Whites to control their story and history. Because most Americans do not regularly encounter Native Americans, the stereotypes associated with these mascots constitute most of their “knowledge” of them. Native protests, however, challenge these by offering an alternative view.

“Native groups (re)claim their identity by countering the clothing of “wannabe” fans with true dress; performing authentic and ritualized drum beats and singing mythic Native songs to juxtapose fans’ tom-tom banging and chanting of the infamous “oh-oh-ohhh” of the Florida State war chant; and demonstrating Native peace–versus fan-conceived red savagery-by protesting with words, not violence.”

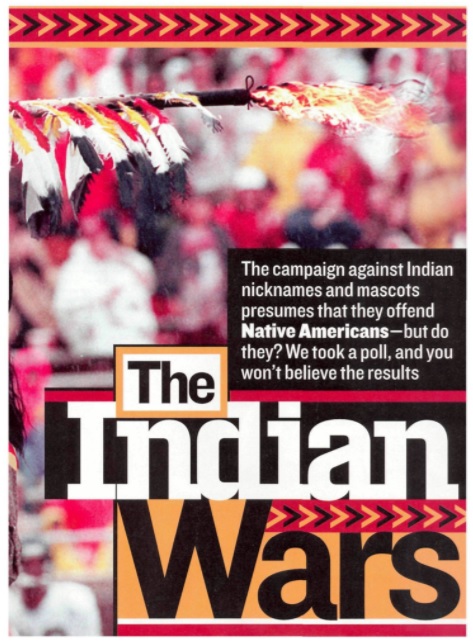

- King, C.R., E.J. Staurowsky, L. Baca, L.R. Davis, and C. Pewewardy. 2002. Of polls and race prejudice: Sports Illustrated’s errant “Indian Wars”. Journal of Sport and Social Issues 26(4): 381-402.

This paper provides a critical review of an article in the March 4, 2002 issue of Sports Illustrated (SI) that argued that Indian mascots are not offensive because most Native Americans support them. The authors point out the biased choice of photographs (mostly White college students in “redface” and no contemporary Natives in normal dress), sensationalistic headlines, complete lack of historical context (e.g. information about the real Osceola), and incomplete reporting (e.g. not all Seminole tribes support FSU). With respect to their poll of “Native Americans,” SI refused to provide any details regarding methodology. The authors’ review of other poll results and the challenges involved in surveying Native populations makes the SI poll seem unreliable. They also question the notion that “popular opinion can settle troubling questions about prejudice, power, and privilege.” They provide a historical review of sports mascots, noting that Indian-themed mascots are second only to animals in popularity, both being chosen for stereotypical aggressiveness.

“Although other ethnic groups have been occasionally used as mascots, these mascots differ from Native American mascots in several ways. The mascots named after other ethnicities are often (a) a people that do not exist today (e.g., Spartans); (b) less associated with aggression (e.g., Scots); (c) selected by people from the same ethnicity (e.g., Irish Americans at Notre Dame); and (d) not mimicked to nearly the same degree.”

They also observe that while “many U.S. citizens see the mascot issue as emerging “out of the blue,” many Native American organizations see the elimination of such mascots as part of a larger agenda of reducing societal stereotyping about Native Americans (in the media, school curriculums, and so forth) and informing the public about the realities of Native American lives. An increase in accurate information about Native Americans is viewed as necessary for the achievement of other goals such as poverty reduction, educational advancements, and securing treaty rights.”

The authors address the argument that Indian mascots “honor” Natives by exploring the “positive” stereotypes associated with the mascots. In reviewing the “bloodthirsty savage” and “noble savage” stereotypes, the authors state:

These two stereotypes convey several problematic notions, including that Native Americans (a) are mainly a people who lived in the past; (b) have not adopted contemporary lifestyles; (c) have a single culture (rather than coming from many different native societies with many different cultures); (d) all were and are involved in fighting, are especially spiritual, and are deeply connected to nature; and (e) that non-Native Americans were and are less involved in fighting.

The authors also list three reasons why some Natives may support the mascots: 1) the stereotypical attributes are sometimes positive; 2) constant exposure to these stereotypes and pressure to acculturate; and 3) economic necessity, seeking to capitalize on the mascots.

The authors then go on to argue that Native mascots in an education setting create a hostile environment in violation of the Civil Rights Act, describing the case of Charlene Teters, Spokane, at the University of Illinois. They conclude by stating that the SI article is an example of White hegemony trying to control the battlefield of ideas.

- Baca, L.R. 2004. Native images in schools and the racially hostile environment. Journal of Sport and Social Issues 28(1): 71-78.

Baca begins by illustrating that “American Indians are treated differently than other minority races,” in that stereotypes, caricatures, and terms that would be offensive and publicly unacceptable for other races are widespread when it comes to Native Americans. Baca then focuses on Native students that attend schools with Indian mascots and the legal recourse they may have under the Civil Rights Act to sue schools that create a “racially hostile environment.” The paper notes “that as of this writing, there has been no successful administrative or court challenge to the use of faux or caricatured American Indian images in schools under these statutes.” The paper explores the legal criteria and the case of Charlene Teters at the University of Illinois, who faced verbal and physical attacks but still lost her case that the environment was “racially hostile.”

- Farnell, B. 2004. The Fancy dance of racializing discourse. Journal of Sport and Social Issues 28(1): 30-55.

Farnell examines statements from supporters of the Chief Illiniwek mascot of the University of Illinois, and especially two representative letters written to the University, seeking the “cultural logic” that allows universities, ostensibly committed to diversity, to promote racializing narratives. Farnell reviews the history behind the “fancy dance,”

which emanated from Wild West Shows and has evolved into modern competitive powwow dancing, but is not associated with Illinois culture. The same can be said for Chief Illiniwek’s Lakota regalia and the “tom-tom” music. Farnell links the students’ fascination with the dance to early-American revulsion and fascination with Native customs and celebration, where “wild dancing and exotic rituals” signified things wild, savage, spontaneous, hypersexual, warlike, and primitive. Such rituals were banned in the late 1800s, only to reappear in Wild West Shows and then in ‘Whiteface’ on football fields. Farnell observes, “The colonialist message was clear: dancing for the entertainment of a White audience was acceptable, but dancing for spiritual and cultural purposes on the reservation was not.”

The aim of Native mascots, argues Farnell, is to objectify Native Americans, define them, and justify the current ‘White public space’ and economic and political order, in which Natives have been removed from their lands and are now outsiders. From the beginning of the Chief Illiniwek mascot, the Chief has modeled “good Indian” behavior: “The drama played out on the football field during the football game against Penn State in 1926, when Chief Illiniwek first appeared and shook hands with ‘William Penn,’… supplies a mythology that reconstructs Indian/White relations as friendly, equal, resolved.” Through impassioned support from alumni, students, and politicians, the University of Illinois effectively creates “a ‘White public space’ in which any contemporary Native American presence is [considered] disorderly.”

- King, C.R. 2004. This is not an Indian: Situating claims about Indianness in Sporting Worlds. Journal of Sport and Social Issues 28(1): 3-10.

In this introduction to a special issue of the journal, King provides an overview and literature review to date. King’s opening paragraph asserts that mascots are “White male students… playing Indian” and notes there are “1,400 educational institutions in the contemporary United States that continue to use such anti-Indian symbols as masks and mirrors, transforming Native Americans into totems (for luck and success on the playing field), trophies (of conquest and the privileges associated with it), and targets (directing hostility, animosity, and longing onto indigenous bodies and societies).” King says that previous analysis (e.g. the papers summarized above) have focused on three key themes:

- They have interpreted Native mascots as “misappropriations and misinterpretations, rooted in antiquated, fictitious, and racist, if often romantic, notions of Indianness.”

- They have analyzed the historical context that have permitted and promoted pseudo-Indian symbols, which position contemporary Natives as “silenced, fixed in the past, opposed to civilization, ranked, studied, problematized, condemned, reinvented, misunderstood, [and] misappropriated” while at the same time assert the dominance of White Americans.

- They have examined the rationale behind the logic and arguments of mascot supporters, focusing on the conceptions of “honor, masculinity, [and] racism”.

King adds to this an exploration of notions of “Indianness,” stating, “It is as if occupying the indigenous other (both fans dressing in feathers and mascots performing at sporting events), Euro-Americans sanction their claim to occupy the land.” The presumed Native traditions, however incorrect, become ‘their’ traditions. In response, Natives have sought to assert their sovereignty by defining themselves differently than these mascots and their institutions. King lists some organizations and government agencies that have come out against Native mascots.

- Springwood, C.F. 2004. “I’m Indian too!” Claiming Native American identity, crafting authority in mascot debates. Journal of Sport and Social Issues 28(1): 56-70.

Springwood explores White claims to Indianness that are made in the context of mascot debates to both support their argument and “to obscure, if not dissolve, Native voices.” Drawing from his own experience at the University of Illinois, Springwood describes a number of examples of pro-mascot activists claiming to be “part” Indian, seeking to legitimize their position and de-legitimize Native opponents. He also examines a 1995 incident in which the university and a pro-mascot television crew approached Peoria tribal leaders, while offering scholarship money, to make statements in support of the mascot. The Peoria leaders gave tepid support, which changed to opposition in future years as they learned more about the mascot.

- Staurowsky, E.J. 2004. Privilege at play: On the legal and social fictions that sustain American Indian sports imagery. Journal of Sport and Social Issues 28(1): 11-29.

Applying legal scholar Felix Cohen’s concept of “transcendental nonsense” to Native mascots, the article concludes with recommendations for how teachers, corporate executives, and government leaders can move beyond Indian mascots and team names toward a more meaningful understanding for both American Indians and non–American Indians. “American Indian sport imagery is, in a literal sense, a concrete example of the loss that all Americans experience by not having an opportunity to truly know about the history and contemporary experiences of American Indians in their rich span and scope.”

- Strong, P.T. 2004. The mascot slot: Cultural citizenship, political correctness, and pseudo-Indian sports symbols. Journal of Sport and Social Issues 28(1): 79-87.

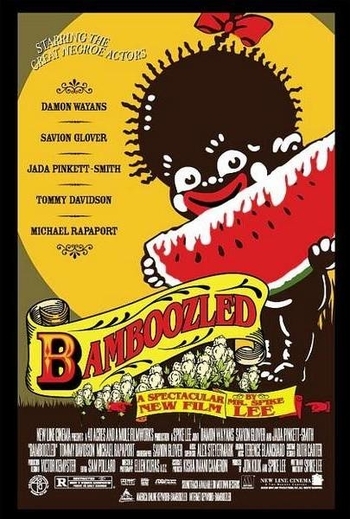

Strong explores “this blatant form of racist representation” by focusing on the double-standard between, for example, Chief Wahoo, and a satirical cartoon image of a smiling black man created by Spike Lee to illustrate a point—so successfully that the image was censored by the New York Times, while Chief Wahoo was routinely published by the paper. Strong focuses on the narrow “cultural citizenship” afforded to Natives, while stating that “the charge of political correctness is a common way of dismissing claims for recognition on the part of subordinated groups—a way of trivializing their interests, visions, and aspirations.”

- Staurowsky, E.J. 2007. “You know, we are all Indian” Exploring White power and privilege in reactions to the NCAA Native American mascot policy. Journal of Sport and Social Issues 31(1): 61-76.

In August 2005, the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) announced a policy that would require colleges and universities with Native American mascots and imagery to refrain from displaying those during NCAA-sponsored events. The policy further stated that institutions with this imagery would be ineligible to host NCAA championships starting in 2006. The action was so controversial, that “noted Cheyenne and Hodolugee Muscogee author Suzan Shown Harjo (2005) wrote in Indian Country Today, ‘The NCAA is learning what it’s like to be mocked, cartooned, lampooned and vilified—in short, what it’s like to be Indian.’”

This article examines what the controversy reveals about White people, power, and privilege. Staurowsky opens by quoting Root (1998): “In a society where land theft is legitimated by law, and where communities and individuals are repressed to facilitate the colonization of territory, the taking up and popularizing of the culture under siege are not neutral acts.” She then goes on to explore White reactions to the mascot controversy, from the Nazi sympathizer that donated $35 million to the University of North Dakota (UND) so long as they kept their Fighting Sioux mascot, to White students who act as if they are “the moral conscience of society,” to UND’s decision to take the $35 million and sue the NCAA. Staurowsky also notes the history of UND in providing military training to fight the Sioux.

- Fryberg, S.A., H.R. Markus, D. Oyserman, J.M. Stone. 2008. Of warrior chiefs and Indian princesses: The psychological consequences of American Indian mascots. Basic and Applied Social Psychology 30: 208-218.

This unique paper reviews four studies that examined the consequences of American Indian mascots and similar images on Native high school and college students. When exposed to Chief Wahoo, Chief Illinwek, Pocahontas, or other common American Indian images, American Indian students generated positive associations (Study 1, high school) but reported depressed self-esteem (Study 2, high school), and community worth (Study 3, high school), and fewer achievement-related possible selves (Study 4, college). The authors conclude that the mascots are harmful because they remind American Indians of the limited ways others see them and, in this way, constrain how they can see themselves.

- Kim-Prieto, C., L.A. Goldstein, S. Okazaki, and B. Kirschner. 2010. Effect of exposure to an American Indian mascot on the tendency to stereotype a different minority group. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 40(3): 534-553.

This paper examines two studies that explored the effect of exposure to Native sports mascots on participants willingness to stereotype other minority groups (in this case, Asian Americans). They conclude, “The current study provides much-needed evidence to empirically evaluate the effects of Native American mascots on creation of a hostile environment. The evidence suggests that the effects of these mascots have negative implications not just for American Indians, but for all consumers of the stereotype. After the Study 1 data were collected, the University of Illinois announced that it would no longer use the Chief Illiniwek imagery in association with its athletics, or allow a performer to dance at halftime events at athletic games (University of Illinois, 2007).”

- Steinfeldt, J.A., B.D. Foltz, J.K. Kaladow, T.N. Carlson, L.A. Padagno Jr., E. Benton, M.C. Steinfeldt. Racism in the electronic agre: Role of online forums in expressing racial attitudes about American Indians. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 16(3): 362-371.

This paper examined over a thousand online comments on newspaper articles about the University of North Dakota’s use of the Fighting Sioux mascot. The paper begins with the history of the mascot, going back to its inception in 1930, and then to the calls for its removal, which began in 1969. [The mascot was changed to the Fighting Hawks in 2015, after being subject to votes by the state legislature, who wanted to keep the Sioux mascot, and the public, who voted to remove it.] They then grouped the online comments into four categories (with the following predominant comments):

- Surprise (“What? This is a problem?”)

- Power/privilege (“We are being victimized by reverse racism and a PC society.”)

- Trivialization (“Changing logo would cost too much.”)

- Denigration/personal attacks (“These people just want attention for their own agendas”)

The paper provides some examples of comments – “Ive [sic] never been racist until now! Im [sic] tired of all your guy’s [sic] crying over this! Perhaps you should spend your time cleaning up the sess pool [sic] of reservations you have created and destroyed. You don’t take pride in your reservations, why would you take pride in a logo?” The study concludes, “the presence of a Native-themed nickname and logo can facilitate the posting of virulent racist rhetoric in online forums, a practice which may flourish…. A daily ritual such as reading the newspaper can subject American Indians to distressing stereotypic representations of their culture.”

- Leavitt, P.A., R. Covarrubias, Y.A. Perez, and S.A. Fryberg. 2015. “Frozen in time”: The impact of Native American media representations on identity and self-understanding. Journal of Social Issues 71(1): 39-53.

This paper focuses on the rare and limited ways in which modern media depicts modern Natives. Because Natives are typically depicted in a stereotypical and historical fashion, Natives gain a limited understanding of what is possible for themselves and how they see themselves fitting in to modern society (e.g. with respect to education and employment). For example, 95.5% of the first 200 images in a Google images search for “Native American” produced historical images. The authors contend that the invisibility of modern Native Americans in the media undermines self-understanding by creating narrow and limiting identity prototypes, and thereby leading to self-stereotyping.

________________________________________________________________________________

Here is the two-minute add created by the National Congress of American Indians to be run during the Super Bowl in 2014. The NFL refused.

As a white man who is most certainly on your side (And you being half Slovakian, arguably some of the whitest people on the planet, you think you’d be a little more understanding unless you are referring strictly to white Americans) you might get more support from us despicable people if you stopped making assumptions and used even-tempered diction and syntax. Saying “Note to white people and others not familiar with this issue:” when “People who are unfamiliar with this issue:” would suffice is offensive to those like me who understand the resentment and who will read on regardless but it immediately repels those who are on the fence about the issue or those on the other side who may be trying to get an opposing view point after doubt begins to form about their current opinion. All they see is more judgement and hatred and what does that do for anyone besides you? You catch more flies with honey than vinegar, as the saying goes.

Nick,

Fair point; I’ve made the suggested edit. Thank you for reading and commenting.