In recent days, Donald Trump has threatened domestic violence against “the left”. In an interview with Breitbart, he said, “I can tell you I have the support of the police, the support of the military, the support of the Bikers for Trump – I have the tough people, but they don’t play it tough — until they go to a certain point, and then it would be very bad, very bad.”

Iowa Republican Senator Steve King posted a Facebook meme that said, “Folks keep talking about another civil war. One side has about 8 trillion bullets, while the other side doesn’t know which bathroom to use.” King added a winking emoji and the line, “Wonder who would win….” Congress recently stripped him of committee assignments over his statements on white supremacy.

These statements come on the heels of the New Zealand mosque massacre, the Pittsburg synagogue massacre, and the Charleston church massacre, targeting Muslims, Jews, and African Americans respectively. It would seem that any surge in violence as described by Trump and King will follow this pattern: attack soft targets. This means people of color or other marginalized groups, in their churches, schools, and social meeting places. It’s a strategy that targets people where they live, kills non-combatants (the definition of “terrorism”), and minimizes the risk to the attacker.

Native Americans are familiar with this. Most of the famous “battles” associated with the ethnic cleansing of Native Americans were attacks by white Euro-Americans on peaceful villages, targeting women and children and male leaders who had just previously declared their peaceful status and cooperation with the whites.

Per instructions from the US Army, Black Kettle was flying an American flag and a white flag of surrender when he was attacked. This image comes from modern remembrance of the victims near the massacre site. Most of the Sand Creek site is now a privately-owned ranch.

One of the most well-known examples of this is Sand Creek, 1864, where Colonel John Chivington, a Methodist pastor, led a group of Colorado volunteers against the Cheyenne and Arapaho camps of Black Kettle, White Antelope, and Left Hand. Under orders of the US government, those Native bands had just reported to Fort Lyon and set up camp. Chivington found them to be much easier targets than the combatant Cheyenne Dog Soldiers he was supposed to be looking for. More than killing combatants, Chivington wanted to make a statement for himself, so he attacked the peaceful villages. He also wanted to target children because, in his words, “nits make lice.” He and his men killed hundreds of women and children and then paraded their scalps, testicles, vaginas, breasts, and fetuses on the streets of Denver to cheering crowds. One man, Captain Silas Soule, refused to participate. He later gave testimony against Chivington and was then gunned down on those same Denver streets.

But the massacre of innocents at Sand Creek was not an isolated incident; it was the norm.

It applies to many, if not most, of the so-called “battles” of the “Indian Wars”. Here’s a few more:

- Washita River Massacre, 1868. Liutenent Colonel George Custer, using General Sheridan’s “winter campaign” strategy to attack villages of mostly women and children hunkered down for the winter in deep snow, attacked Black Kettle’s band of Southern Cheyenne (the same group from Sand Creek). Black Kettle was seeking peace and had just returned the previous day from Fort Cobb, where he had said, “We all want peace, and I would be glad to move all my people down this way; I could then keep them all quietly near camp. My camp is now on the Washita, forty miles east of the Antelope Hills, and I have there about one hundred eighty lodges.” Custer attacked at dawn, killing many women and children, as well as Black Kettle and his wife. Fifty-three women and children were captured and used as human shields and hostages.

- Marias Massacre, 1870. Seeking to avenge the murder of a white fur trader, Major Eugene M. Baker and his troops surrounded a band of Piegan families in their winter camp in deep snow. When informed by scout Joe Kipp that this was a peaceful group under protection of the US Army, Baker deliberately ignored the information, threatened to shoot Kipp, and said “That makes no difference, one band or another of them; they are all Piegans and we will attack them.” Kipp shouted to warn the Piegan, but the men under Baker opened fire and killed over two hundred. Only fifteen were men. Fifty were children under the age of twelve.

- Camp Grant Massacre, 1871. The Tucson Committee for Public Safety, a local white militia with support from Mexican Americans and a rival tribe, attacked a peaceful band of Pinal and Aravaipa Apache who were living near a US Army fort. One hundred forty-four Apache were killed and mutilated, of which only eight were men. Twenty-nine children were sold into slavery. In response, President Grant condemned the attacks and brought the perpetrators to trail. The jury found them not guilty after nineteen minutes of deliberation.

- Looking Glass’s Camp, 1877. While Chief Joseph had resolved to fight for the Wallowa Valley (which was only included in the demands of the white settlers because of a poorly drawn map) Looking Glass resigned to move to the new reservation. But the US Army, under General Howard, decided to be sure and preemptively arrest Looking Glass. In the process, they opened fire on his camp, killing an elder, while a woman and child drowned in the Clearwater River trying to escape. In a result all too common with attacks on peaceful villages, the rest of Looking Glass’s band abandoned their non-violent strategy and joined Chief Joseph in the fight for their land.

- Wounded Knee Massacre, 1890. The Sioux had already been confined to concentration camps (“reservations”) for a dozen years when the Ghost Dance revival swept through, a religious re-awakening of Native culture. Afraid of the movement, the US Army called Spotted Elk’s band of 350 back to Pine Ridge. They were en route returning when they were attacked by the US Army 7th Cavalry. In the dead of winter, they massacred 300 Lakota, mostly women and children, buried them in mass graves, and bragged that they had avenged Custer’s defeat at the Greasy Grass (Little Bighorn) fourteen years earlier.

I’m leaving out the Bear River Massacre of 1863, as well as countless smaller examples, such as an attack on a small group of surrendering Lakota near the Black Hills in the 1870s. This kind of thing happened a lot. The white flag of peace was an easy target. So were women and children. In nearly all the battles between Natives and the US Army, the Natives had their families with them. The US Army didn’t and came to consider this the Natives’ greatest handicap. In addition to “winter campaigns” where entire villages were holed up in snow, they knew that Natives would quickly surrender if the risk to their women and children was unacceptable. When the US Army came upon Chief Joseph’s peaceful band fleeing to Canada, they surrounded their tipis in the night and gave the order to “aim low”.

If history, both past and recent, is any guide, the lessons from these experiences are sobering. The road of peace and surrender is a dangerous one. When race is involved, when the motivation is ethnic cleansing or genocide, women and children are targets, possibly even more than men.

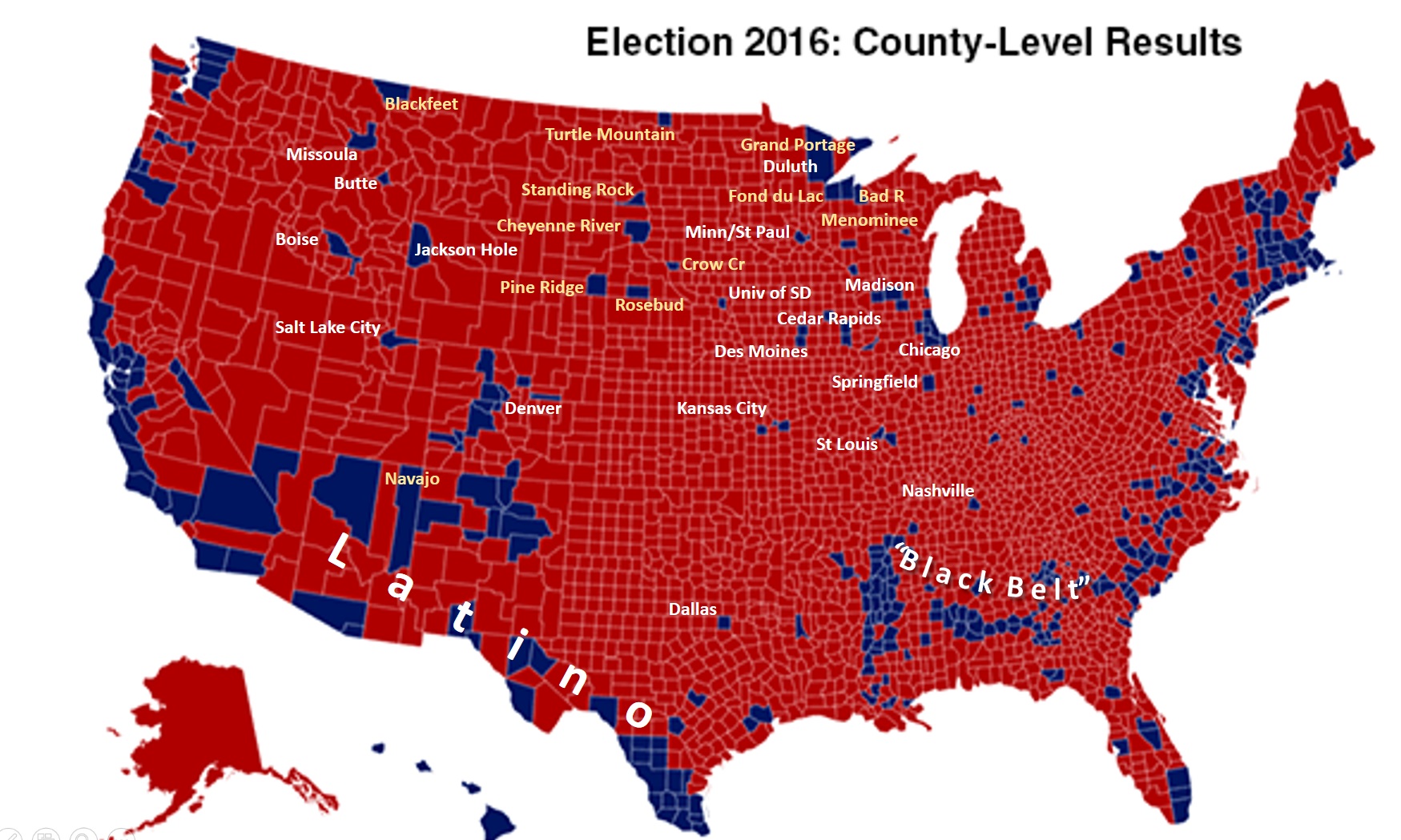

2016 presidential election results by county. While Hilary Clinton won the urban islands, Black, Latino, and Native vote, Trump won the rural areas, vast tracts of formerly-Native land now controlled by angry white supremacists. In this context, the Native reservations appear to be the most isolated and vulnerable of all.