Obama’s Play

On December 4, 2016, during that short window between Hillary Clinton’s loss and Trump’s inauguration, the US Army Corp of Engineers, at the direction of lame duck President Barack Obama, announced that construction on the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) would be suspended pending the Corps’ “reconsideration of its statutory obligations”. The water protectors at Standing Rock celebrated with fireworks over the snowy encampment.

December 4, 2016. The judge’s ruling essentially returns us to this night.

The Army Corps’ statement, in and of itself, was not legally binding; it was just a policy announcement. All that changed, however, on January 18, 2017, about 48 hours before Trump took office, when a Notice of Intent to initiate an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) was published in the Federal Register, opening up a public comment period. An EIS is a full analysis of all potential environmental impacts and ways to reduce those impacts. And this analysis must be done for several options. For DAPL, that would mean looking at alternative routes. (More on the EIS process here.)

The original route (dashed line) took the pipeline too close to Bismarck for their comfort, so the route was secretly changed, without public hearings, to the reservation area.

This was not just a legal trick; it was the right thing. Up until then, the primary permitting document was an Environmental Assessment (EA). An EA is the little brother of an EIS. It’s what you do when a project is unlikely to have any environmental impact. The idea that a 1,172-mile long pipeline crossing four states and several major rivers did not need an EIS was ludicrous.

Less than a week later, now President Trump issued his memorandum, ordering the US Army Corp to approve the pipeline as soon as possible “to the extent permitted by law.” But Obama had already painted him into a corner by starting the EIS process.

Nevertheless, the Corps obeyed and moved forward. It stopped the EIS process (without justification), granted the pipeline permit, construction was completed, and oil commenced flowing in May 2017.

Standing Rock pressure

But the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, partnering with the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, continued to challenge the pipeline in court. Because they had stopped an EIS process that had already started without any new information, leaving a flimsy EA as its primary permitting document, DAPL was legally vulnerable. The tribes, with Earthjustice as their legal team, hired experts to shred the EA as insufficient. They were successful.

US District Court Judge Boasberg has overseen the entire case. The tribes’ scientific experts pointed out so many flaws in the EA that the project met the EIS bar of “highly controversial” (based on the science, not the protesters). Boasberg was especially influenced by the assessment of spill risk, stating, “the impact of a spill has been one of the Court’s central concerns throughout the case…. systems may not be in place to prevent that spill from becoming disastrous…. DAPL’s leak-detection system was incapable of detecting leaks of less than 1% of its flow rate, meaning that 6,000 barrels per day could leak without triggering an alarm.”

After many hearings and various twists and turns, in March 2020, Judge Boasberg found that “Defendant U.S. Army Corps of Engineers had violated the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) when it granted an easement to Defendant-Intervenor Dakota Access, LLC to construct and operate a segment of that crude-oil pipeline running beneath the lake.” In short, the Army Corps needed to do an EIS. The judge returned us to the days before Trump’s inauguration.

The role of COVID

An EIS can take one to five years to complete. The question was: should the pipeline be shut down in the meantime?

On July 6, 2020, Judge Boasberg said yes, all oil must be removed from the pipeline within 30 days. (Link to the judge’s order.)

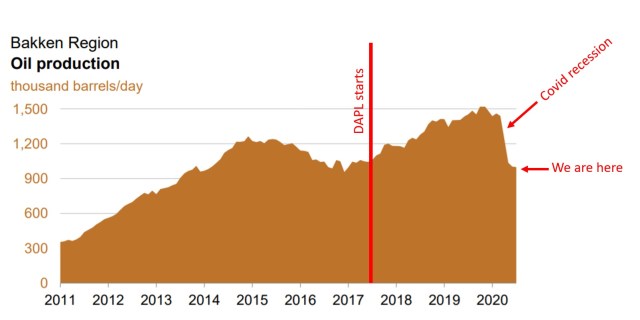

Note that, since the opening of DAPL three years ago, Bakken oil production increased from about 1,000 Mbbl/day (thousand barrels/day) to 1,500 Mbbl/day. That increase is largely explained by DAPL, which carries 570 Mbbls/day.

Bakken production today is less than it was when DAPL operation began.

According to Boasberg’s ruling, “Dakota Access’s central and strongest argument is that shutting down the pipeline would cause it, and the industries that rely on it, significant economic harm, including substantial job losses.” This meant that many North Dakota oil producers, with no way to get their oil to market, would have no choice but to ‘shut in’ some of their wells causing a 34.5% decline in North Dakota crude production (back to 1,000 Mbbl/day).

But here’s where the pandemic came in. The COVID-induced decline in demand for oil has caused a decline in production more than what for Energy Transfer Partners (ETP) was predicting, reducing oil production down to pre-DAPL levels. In short, the pipeline serves no purpose now.

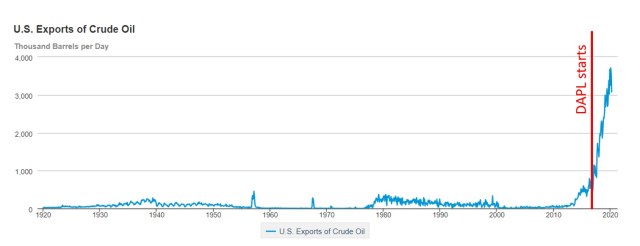

Furthermore, the public never depended on DAPL for oil supply; it was all about profits for ETP and Sunoco. This oil was likely exported.

Since the US began allowing the widespread exportation of crude oil, exports have grown from less than 1,000 Mbbl/day before DAPL to over 3,500 Mbbl/day at the start of 2020. The new production created by DAPL fits easily within this increase, suggesting the new oil moved thru DAPL is essentially exported.

Judge Boasberg pointed out that the Corps estimates the EIS process will take 13 months, during which time the DAPL oil is unlikely to be missed by anyone (except ETP).

Judge Boasberg wrapped up his ruling with these choice quotes:

Without [shutting down the pipeline], the Corps and Dakota Access would have little incentive to finish the EIS in a timely matter. When it comes to NEPA [the environmental law] , it is better to ask for permission than forgiveness: if you can build first and consider environmental consequences later, NEPA’s action-forcing purpose loses its bite.

The Court does not reach its decision with blithe disregard for the lives it will affect. It readily acknowledges that, even with the currently low demand for oil, shutting down the pipeline will cause significant disruption to DAPL, the North Dakota oil industry, and potentially other states. Yet, given the seriousness of the Corps’ NEPA error, the impossibility of a simple fix, the fact that Dakota Access did assume much of its economic risk knowingly, and the potential harm each day the pipeline operates, the Court is forced to conclude that the flow of oil must cease… within 30 days.

What’s next?

The Army Corps and ETP will appeal, possibly to the US Supreme Court.

And an EIS process may start. It will begin with a public comment period on what issues should be addressed (such as environmental justice issues associated with various route options, or whether the pipeline should be used at all). (More on the EIS process here, something I posted back in 2017 when the EIS process started the first time.)