As the American Ornithological Society (AOS) contemplates changing potentially dozens of English bird names to names more representative of the bird, and more inclusive of our society, many have voiced interest in and support of indigenous bird names.

This post is a deeper dive into that topic. Its primary audience is me. I’ve been invited to participate in AOS’s ad-hoc committee to come up with the process to change bird names, and this topic came up already at our first meeting. I’m trying to learn more about it. The second audience are Native birders or biologists that have thoughts about this. Please contact me or add to the discussion in the comments. I really want that. The final audience is the larger public, just so everyone is aware of the issues.

Let’s begin.

Types of indigenous bird names

Indigenous bird names could mean several different things:

- The actual name of the bird in an indigenous language

We have many examples of this from Hawaii – the `i`iwi, `elepaio, and ‘amakihi, etc. On the mainland, sora, condor, ani, kiskadee, and tanager are indigenous names (more on that below). I’ve heard that chickadee (and possibly towhee) may be derived from the Cherokee tsigili’I, or they may simply be independent attempts to mimic the bird’s call (an onomatopoeia), like killdeer or chachalaca. In the mammal world, raccoon, moose, and skunk are all derived from Algonquin words.

- An English translation of an indigenous name

Another option is to take the meaning of the indigenous name and translate it into English. For example, the Iñupiaq word for Steller’s Eider is Igniquaqtuq. This translates to “duck that sat in the campfire”, a reference to its dark orange underparts. An anglicized form of the name would be Fire Eider or Campfire Eider. The AOS’s task is, after all, to revise English bird names. This name is English, but derived from an indigenous name.

- A name using an indigenous word

The recently described Inti Tanager in South America is an example of this. A bright orange-yellow bird, Inti refers to the Incan sun god. Another example is the Montezuma Quail, referencing its range centered in Mexico. The Steller’s Eider version of this might use the actual Iñupiaq word for the bird, such as Igniquaqtuq Eider.

- A name based on the name of a tribe

Examples would be Aztec Thrush and Inca Dove. The Norwegians eschew most American honorifics in their names for American species. Bendire’s Thrasher is navahospottefugl, or Navajo Thrasher; Cassin’s Sparrow is apasjespurv, or Apache Sparrow; and Brewer’s Sparrow is shoshonespurv, or Shoshone Sparrow.

The AOS’s Ad Hoc Committee for English Bird Names, of which I was a member, recommended changing the name of Inca Dove because it is “widely considered to have been given in error because of confusion by the dominant culture between the geographic locations of the Inca and Aztec civilizations.”

Likewise, the same committee recommended changing Eskimo Curlew, noting that “’Eskimo’ is a dated term for Indigenous peoples of the far north, now considered offensive.” The US government switched from Eskimo to Alaska Native in official terminology years ago. The term encompasses multiple people groups (e.g. Iñupiat, Yupik, Aleut).

Current bird names with indigenous roots

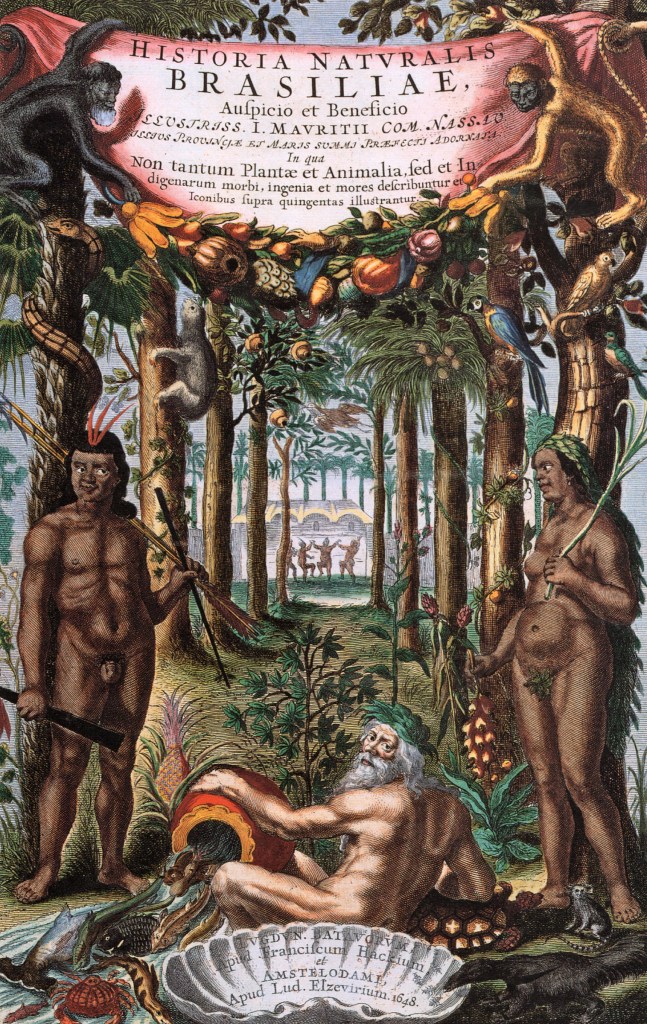

There are several North American birds that currently have English or Latin names with indigenous roots. Almost all of these names come from south of the US border, indicative of a different social dynamic when they were described by Europeans.

Birds with English names derived from indigenous words

- Sora – derived from “soree” based on its call, from the Virginia region, so probably an Algonquin-based name.

- California Condor – Condor is a Quechuan word.

- Montezuma Quail – Montezuma is derived from Moctezuma, the last ruler of the Aztec Empire, and now widely used as a surname in Mexico.

- Inca Dove – After the people group from Peru, though the species’ range is primarily in Mexico. Possibly intended to be Aztec Dove?

- Ani – The Tupi name for the species. The Tupi were one of the most numerous peoples of pre-colonial Brazil. They are related to the Güaraní.

- Kiskadee – The Tupi nickname for the species.

- Aztec Thrush – After the people group from Mexico.

- Tanager – The Tupi word for various colorful songbirds.

Birds with Latin names derived from indigenous words

- Snowy Egret – thula is Araucano for Black-necked Swan, applied to the egret in error.

- Roseate Spoonbill – ajaja is the Tupi name for the species.

- Limpkin – guarauna is the Tupi name for the species.

- Emperor Goose – canagica is said to derive from an island and people group in the Aleutian chain, though there is no island by that name or a similar name.

- Franklin’s Gull – pipixcan is Nahuatl (Aztec) for gull.

- Great Kiskadee – Pitangus is the Tupi name for the family.

- Green Jay – yncas refers to Inca. The southern part of their range includes the lands of the Incan Empire.

- Tropical Parula – pitiayumi is the Güaraní name for the species.

- Hepatic/Summer/Scarlet/Western/Flame-colored Tanager – Piranga, the genus name, is the Güaraní word for various colorful songbirds.

Some guidance

Whatever route a future naming committee takes, there are two issues to keep in mind:

- Bird ranges and indigenous lands do not map perfectly to each other.

This is immediately apparent to most. There are over 500 federally-recognized tribes in the United States, and hundreds more terminated and fighting for re-recognition, or never recognized at all. Bird ranges typically cover the traditional lands of many tribes.

Taking an example from above, the range of the Brewer’s Sparrow, called the Shoshone Sparrow in Norwegian, is indeed centered on traditional Shoshone lands. At least the breeding population. But it also includes some Paiute, Umatilla, Walla Walla, Salish, Blackfoot, Crow, Cheyenne, Lakota, Arapaho, Ute, and Navajo land – and others. The wintering grounds are centered on Tohono and Hia-Ced O’odham, Cochimi, Apache and other lands. This is a typical situation. Not that Shoshone Sparrow is a poor name. It’s probably the best fit if you needed to choose one tribe. And we do have California Condor, California Gull, Carolina Wren, Oregon Junco, Tennessee Warbler, Connecticut Warbler, and many others who do not really fit the territory of their name. But those are all misnomers. It seems to me the range/territory should be a tight fit to go this route.

This type of name could be considered for species with a very limited range. Gunnison Sage-Grouse, for example, fits entirely within Ute lands, with no overlap to other lands (as best I can tell). While Gunnison is a “second-order” honorific (that is, named after a place named after a person), it could accurately be called Ute Sage-Grouse.

And I’m not even including one important caveat. Just like in Europe, lands and territories of different people groups have shifted through history. All those maps you see of traditional native lands (this is one of the better sources), those are just snapshots in time.

In some cases, focusing on language may be easier. Many adjacent tribes descend from the same language group, and thus words in their languages may be very similar. Algonquian-based languages, for example cover much of the Midwest and Northeast.

- Tribal Consultation

After years of being subject to external government and academic studies, many resulting in insulting and incorrect stereotypes, tribes have an expression: “Nothing about us without us.” For government entities, it’s a legal requirement. If you’re going to do anything about or involving a tribe, talk to them first. Most tribes have a department of natural resources, or something similar, which would be a good starting point. They will direct you to the right people.

My other posts on this topic

Bird names matter: Top ornithologists and organizations endorse name changes for all species named after people — my summary of the 2021 AOS Congress on English Bird Names.

Honorific bird names facts and figures — some basic background information about where all these names came from.

The fun part: New bird names — my proposals for new names for 82 species, plus what they are called in other languages.

Reflections of a Native birder: The one Indian killer bird name I really have trouble with — about Scott’s Oriole, the Trail of Tears, and my family.

Pingback: Nationwide group relooks at 152 birds named after folks – The News and Finance

Hello, I am looking for information on Macushi and Wapishani language names for birds in the Rupununi region of Guyana, South America. Would you be able to suggest any research sources in this area? Thanks much for your time in considering this. – Daniel

Sorry, I have no idea. But I’m interested in what you find!

Pingback: Renaming Birds: Steller’s Eider – Christina Wilsdon