The contradictions of JD Vance are well-known. He once called Trump “a bad man, a morally reprehensible human being.” Now he’s allied with Trump. He claims to come from a poor region, yet embraces policies that will further exploit and impoverish them.

From the lands Vance claims to know so well, there is an alternative political ethos – a Native one.

The false elegy

Vance calls his book an elegy, but it’s not really a mournful lament. The New Republic described it as “a list of myths about welfare queens repackaged as a primer on the white working class.” Following white conservative tropes, it blames the poor for laziness – for their failure to pull themselves up by their bootstraps, as he did. Everything white people say about Blacks or Natives, Vance says about poor whites. But just because he’s white, it doesn’t make it legitimate.

In retrospect, the book was a self-serving, politically-contrived memoir designed to position him for future campaigns. Using no actual data or economic analysis, he presents himself as proof of hard work, while blaming government services for making people lazy, while acknowledging that both he and the grandparents that raised him benefited from some of these services, while now planning on cutting those services. He says he supports unions, but was scored a 0% by the AFL-CIO’s Legislative Scorecard.

In his climb to the top, he set up a charitable organization to fight opioid abuse, but the funds were largely diverted to his campaign advisor. The same charity also worked with Purdue Pharma, whose predatory dispersal of OxyContin so decimated Appalachia that the life expectancy of the entire US declined. In its communication, the charity watered down connections between Purdue Pharma and opioid abuse.

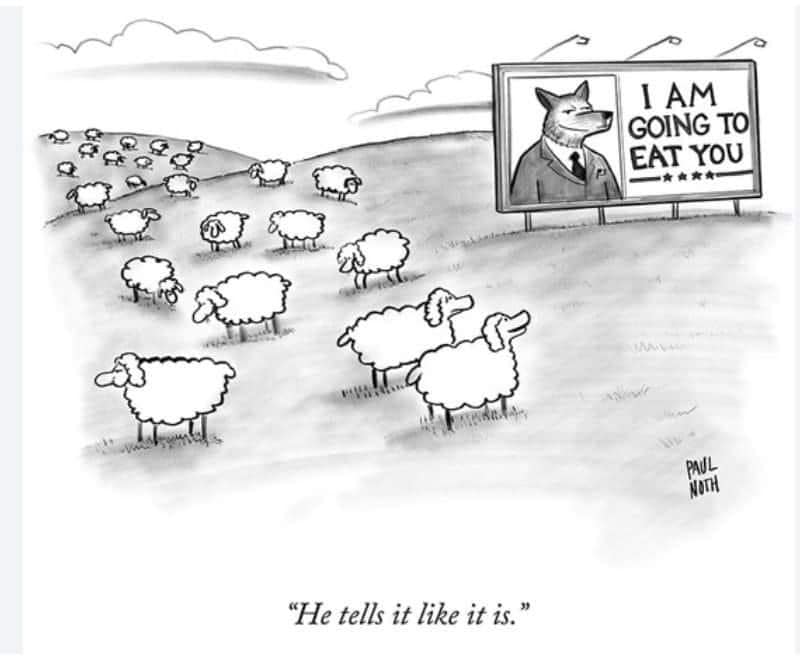

What Vance is to Appalachia is what a fox is to a henhouse. And that’s just with regard to white people. Black people hardly exist in his book. There is no discussion of white retractions of public services when faced with sharing them thru integration, no mention of the conjoining of racism and accusations of so-called socialism.

Vance’s erasure of Blacks is the point, because, according to his book, Trump’s 2016 nomination and election had nothing to do with race. Apparently, that’s the explanation that white liberals wanted. Even though the polls, surveys, and research – as well as Trump’s own rhetoric, both then and now – pointed to white supremacy to explain Trump’s cult-like support, Vance gave white liberals an opportunity to reach across the aisle, avoid race, and feel the pain of the poor white working class. Blacks didn’t buy this premise. Neither did whites from Appalachia.

In fact, his book was most critiqued by Appalachians themselves. In a 2017 review for the Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition, Janet Keating wrote, “The lack of ambition and control Vance refers to is not the fault of Appalachians. The years of systemic exploitation and heavy-handed control by the extractive industries, and the political establishment that kowtows to these industries, underlies the generational poverty, domestic violence, and current drug/alcohol addiction.” The coal industry literally removed Appalachian mountaintops, devastated their forests and streams, made billions, and left their workers impoverished. John Prine’s 1971 song “Paradise”, about the Peabody coal mine, remains as relevant as ever.

Another reviewer noted that the once thing “Vance expresses continually throughout his book, is how absolutely brilliant he is compared to almost everyone else.”

One can see how this would endear him to Trump. Together, their main policies – discouraging and deporting immigrants, jacking up tariffs on foreign goods, and creating a weak dollar – would fuel inflation. And that’s according to the conservative American Enterprise Institute.

Perhaps Vance’s greatest contradiction is that he never lived in Appalachia. He was born and raised in Middletown, Ohio, a suburb just north of Cincinnati. When his grandparents raised him, they came to Middletown and left Appalachia behind.

The Indigenous critique

My family, if you go back far enough, is also from Appalachia. In fact, we claimed much of it until the Trail of Tears. I’m an eighth-generation descendant of Nanyehi, aka Nancy Ward, one of the great leaders of Cherokee Nation. It’s hard for me not to superimpose Vance onto the Appalachia of a traditional Native society. I imagine him seeking leadership. He would not fare well.

Though cultures and societies varied across Turtle Island, political structures often employed a gender-based balance of powers. In simplified terms, most leaders were men, but only women could vote. Clan matriarchs selected chiefs and leaders and could remove them from office at any time.

In 1765, when Cherokee leader Attakullakulla met an English negotiating party, his first question was, “Where are your women?” He likely had Nancy Ward at his side. Because the English had arrived at the treaty table without women, he assumed they were not serious about the negotiations.

Not only did the Cherokees and other tribes have women leaders before the US even existed, the power of women was integral to Native societies across much of the Americas. Many had matrilineal societies; some still do. Rights and possessions were passed down thru the mother’s line. Traditionally, upon marriage the groom moved into the family compound of the bride. One British fur trader warned his friends about marrying in, because “the women Rules the Rostt and weres the brichess.” European women, meanwhile, lived in near servitude.

Vance, who has embraced traditional families (as defined by white culture) and abortion without exception, and dismissed the gravity of violent relationships, would face a chilly welcome among traditional Native in-laws.

The social power of Indigenous women was – and still is – a reflection of their prominence in Native cosmology. Female goddesses and spiritual beings abound, often with the greatest significance. The concept of “Mother Earth,” a distant echo in European cultures, remains foundational in Native circles, where it has political significance. Among the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois), Sky Woman helped create the terra firma we stand on.

Fascism, and indeed any orders from tribal leaders, were not acceptable. Tolerance and respect for individual rights were so paramount in traditional Native America that anyone could decline an order without fear of force of law. In 1695, the Ojibwe leader Chingouabe explained to the French governor, “It is not the same with us as with you. When you command, all the French obey you and go to war. But I shall not be heeded and obeyed by my nation in like manner.”

Native governing authority was by persuasion. As noted by Benjamin Franklin, “Their government is by counsel of the ages; there is no force, there are no prisons, no officers to compel obedience, or inflict punishment.” It’s no coincidence that many historical Native leaders – Tecumseh, Quanah Parker, Canassatego – were described as powerful orators.

These Native political and social customs were communicated to Europe via diaries from Jesuit priests (the Jesuit Relations). They went viral. In The Dawn of Everything, David Graeber and David Wengrow describe this as the “Indigenous Critique” of oppressive European societies. It inspired the French Revolution. Liberté, égalité, fraternité.

This is not to say Native societies were primitive anarchies or utopian communes. Surely they had problems, but they were held together by a complex web of kinship relationships. Villages, clans, tribes, and matriarchal lines wove through each community, interlocking them.

In Native America, the measure of a leader was how much they cared for their people. The historic footprints of the great Shawnee chief Tecumseh undoubtedly crossed some of the same paths as Vance in the Ohio Country. Anthony Shane, a French/Odawa relative of Tecumseh, said that he “was remarkable for hospitality and generosity. His house was always supplied with the best provisions, and all persons were welcome and received with attention. He was particularly attentive to the aged and infirm, attending personally to the comfort of their houses when winter approached, presenting them with skins for moccasins and clothing…. He made it his particular business to search out objects of charity and extend the hand of relief.”

In the eighteenth century, when Native American dignitaries visited London and Paris, they were shocked at beggars in the streets, puzzled how these obviously wealthy societies ignored their own people.

This community ethic continues to this day. My own Cherokee Nation pours its revenues into education and healthcare, some of which are available to non-tribal citizens living within the reservation.

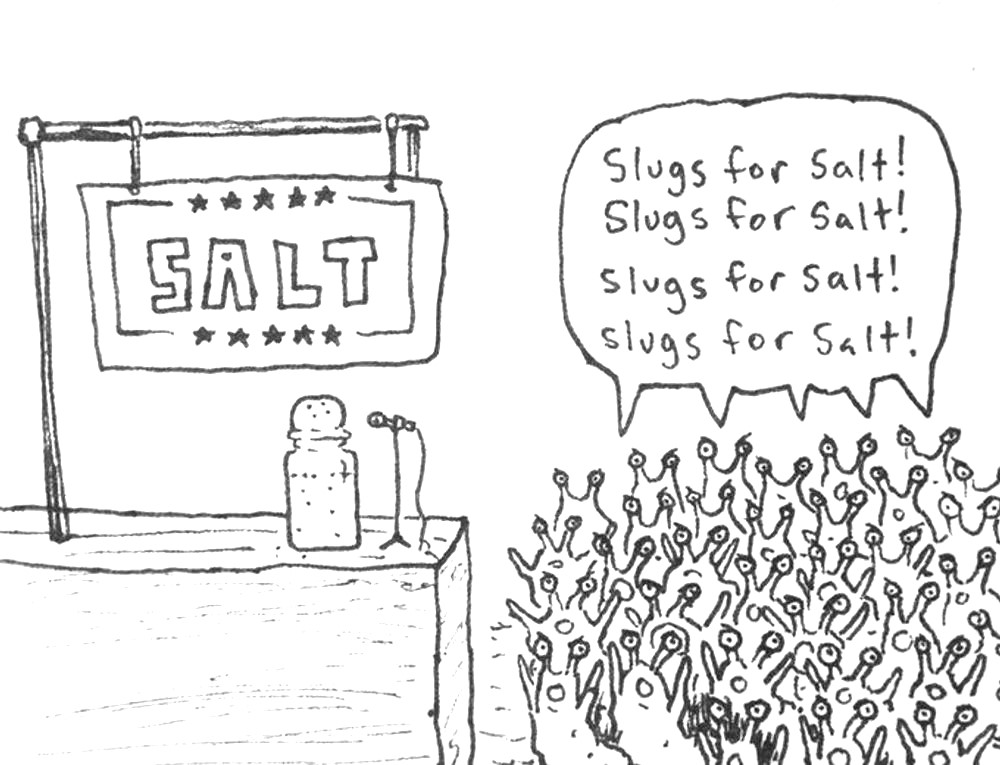

In 2016, Vance criticized Trump, saying he was “leading the white working class to a very dark place.” But now he has joined that black road. His Venmo transactions show close connections to The Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025, which threatens to weaponize federal enforcement agencies into tools of personal and political retribution. Trump promises that, should he win this election, there will be no more elections. Vance has ridiculed Indigenous Peoples’ Day, calling it “a fake holiday to sow division.”

This is my lament, my elegy – that the Cherokee homeland, the Appalachians, and all of America, have come a long way from the world of Sky Woman. Rather than the authoritarianism of a white male ethnostate, the land and the people need leaders that reflect traditional Indigenous values. A version of the Haudenosaunee criteria for leaders reads: “The Lords of the Confederacy of the Five Nations shall be mentors of the people for all time. The thickness of their skin shall be seven spans — which is to say that they shall be proof against anger, offensive actions and criticism. Their hearts shall be full of peace and good will and their minds filled with a yearning for the welfare of the people of the Confederacy. With endless patience they shall carry out their duty and their firmness shall be tempered with a tenderness for their people. Neither anger nor fury shall find lodgment in their minds and all their words and actions shall be marked by calm deliberation.”

If leaders do not live up to this, the women will remove them from office. Or prevent them from getting there in the first place.

May it be so.

I’ve been reading your posts since I found you when I was trying to figure out what happened with Julie Jaman at the pool. You posted sort of a daily journal, and it showed me what was going on, and also made me want to subscribe to “Memories of the People.” I continue to be fascinated by your work and the history you present. I wonder if you’d consider a Substack newsletter? It’s very interactive and you could post every piece you’ve ever posted for, eventually, a larger audience. I think what you write about is essential. Just a thought. Thanks for what you do and who you are. ~Kirie

Siyo from Sequoyah County…That article was exceptional!!!

wado!