Last week I saw one of the largest mass burial sites in the United States. It is unmarked.

The location is the fields among the rolling hills and gentle pastures just south of Charleston, Tennessee. This is where 9,032 Cherokees were forced to encamp in preparation for “Indian Removal” – the official name for the US government’s policy of ethnic cleansing in the 1830s.

Backstory

For the Cherokees, the Trail of Tears began suddenly, on May 26, 1838, when General Winfield Scott ordered his soldiers to begin going door to door, house to house, farm to farm, cabin to cabin, rounding up 16,000 people at gunpoint and marching them to stockades hastily built across portions of Alabama, Georgia, Tennessee, and North Carolina. The majority of Scott’s men, 5,180 out of 7,380 (70%) were from local militias with a vested interest in pillaging Cherokee property. As such, they gave people little time to gather possessions or even a spare change of clothes.

Among white Americans, the Indian Removal Act had been extremely controversial when it passed Congress by a few votes in 1830. During the presidential election of 1828, mass deportation was one of the top issues. Ironically, the margin of victory came from the extra votes that southern states had in the House of Representatives because their Black slaves counted as 3/5ths of a person. The ethnic cleansing of Native Americans then paved the way for a massive increase in slave plantations across the Black Belt of the South. The US Constitution thus created a system in which Black representation was used against them.

Eight years into the project, Indian removal was still controversial. Scott, one of the top generals in the US Army, was only in charge of the Cherokee removal because his underling, General John Ellis Wool, asked to be relieved of the duty. Wool even threatened to resign his commission. Likewise, Brigadier General R. Dunlap threatened to resign. Like many in the area, he was personally acquainted with many Cherokees.

The Concentration Camp

From the start, plans went awry. The first three detachments of Cherokees, each with about a thousand people, departed from Ross’s Landing (Chattanooga) on flatboats down the Tennessee River. But the summer was hot and dry and the river was low. The boats floundered and people began to die.

At this point, the Cherokee government intervened and asked General Scott if the operation could be delayed, and if the Cherokees could supervise their own ethnic cleansing, waiting until fall when the weather was cooler and rains enabled ferries to cross the rivers.

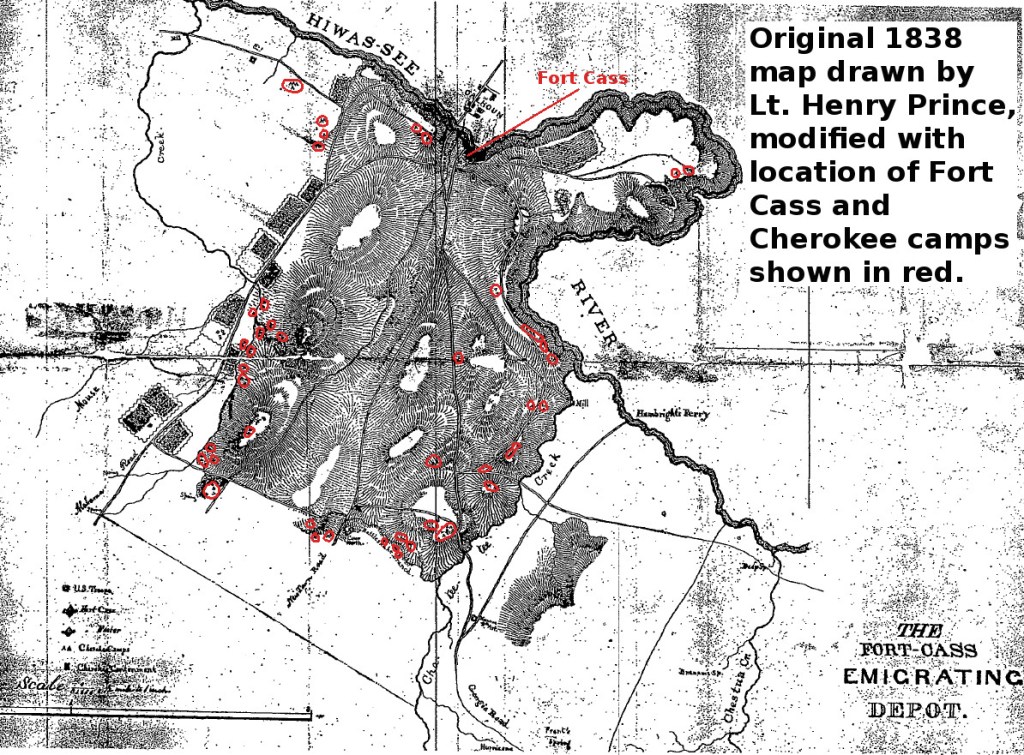

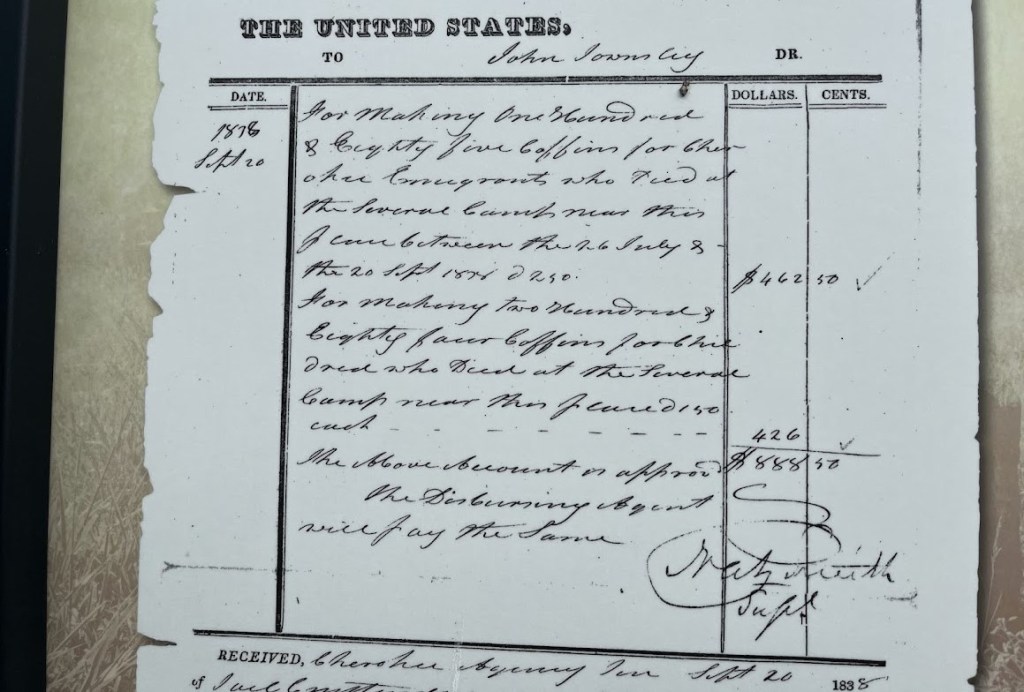

Scott consented and moved most of the rest of the Cherokees to Fort Cass at the Cherokee Agency (now Charleston, TN) along the Hiwassee River, the border between Cherokee Nation and the United States. From here, they could cross the Tennessee River at Blythe’s Ferry and take an overland route to Indian Territory (Oklahoma). The expenses were tracked and reimbursed, making it one of the most well-documented genocides in history. We have the invoices and receipts.

With a long, hot summer of waiting ahead of him, Scott wanted to “parole” the Cherokees, to send them back to their homes with a promise to return. But this was no longer an option. Across Cherokee Nation, white settlers had already moved into their homes and cabins, taking over barns and livestock, furniture, household goods, and even bedding and clothing left behind. Furthermore, the state of Georgia promised to hang any Cherokees found within their borders.

And so the majority of the Cherokees – 9,000 out of 16,000 – ended up at Fort Cass, stuck in the encampments on the south side of the Hiwassee River. This included many mixed families with white fathers. Measles, dysentery, and whooping cough began to spread through the camps “to a great and deplorably fatal extent,” to quote Captain John Page of the US Army.

Missionary Elizur Butler estimated 2,000 people died in the camps that summer. Subtracting the number that was counted in the camps (14,870) from the number that eventually departed on the various detachments that fall (13,111), 1,759 are missing. Those are the presumed dead.

For me, this was a home-going trip. I was in this area for the annual Trail of Tears Association conference. Over 200 of us attended, half of us Cherokees, seeking to connect with each other and learn details of our ancestors. It was my first time to visit the Cherokee homeland. In fact, I think I may have been the first to return since the Trail of Tears. I’m pretty sure that neither my father nor my grandparents, all born in Oklahoma/Indian Territory, ever made the journey.

The other half of us seemed to be allies, mostly academic researchers and dedicated government agency staff, seeking to tell our story to the public. We saw some new memorials, monuments, signs, and displays educating the public. They were generally well done.

As we drove toward the Hiwassee River Heritage Center in Charleston, the locations of the camps were pointed out. We couldn’t stop – it was a narrow county road with no shoulder. And there were no signs telling us what was there. All we saw were open pastures and rolling hills. I asked Jack Baker, Cherokee historian and the guide for our trip, about those hundreds of coffins on the invoice and the thousands of deaths in the camps. “Where were they all buried?” “Out there,” he said, with a wave of his arm, “they couldn’t take them with them.”

Honestly, I never expected to be standing at a mass burial site. I never realized that approximately half the deaths associated with the Cherokee Trail of Tears happened at one place – in these fields – before the main journey had even begun.

Mass graves in the US

Nearly all of the graves are likely on private land, mostly pasture or corn fields with scattered homes. Some of the landowners have been there seven generations, dating back to 1850. There are communications with some of them, who have voiced a desire to leave the graves undisturbed, but there are no laws to ensure that. The Native American Graves and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) only applies to federal land. Though it would surely qualify, National Historic Landmark designation requires the landowners’ consent. Legally, there is nothing to stop them from plowing up the remains. Talking with Cherokees involved with protecting such sites, they said the path of least resistance is often to talk with the landowners and arrange for a land trust organization to acquire the land or purchase an easement protecting the sites.

This issue is not unique to this site. Across Indian Country, from Sand Creek to Camp Grant to Whitestone Hill, only portions of the resting places of our ancestors are protected. Others, such as Wounded Knee, Bear River, and Mystic, have been acquired by the affected tribes.

At Fort Cass, we don’t even know the exact locations of the burial sites. This is not unusual. Finding them requires ground-penetrating radar surveys. That’s a slow process. Just surveying an area the size of a basketball court takes hours. Such work also requires funding. And it also requires permission of the landowners.

This all contrasts strongly with white gravesites. At St. Clair’s Defeat in 1791, when hundreds of US soldiers were killed by a pan-tribal alliance, the dead were found and re-interred within a few years. A huge monument in the town of Fort Recovery, Ohio, honors them. Likewise, at the Battle of Little Bighorn, aka Custer’s Last Stand and Greasy Grass, white bodies are considered sacred. A federal site protected by the National Park Service, the battlefield has been subject to an immense amount of research and study to identify the precise locations where each and every US solider fell.

But Black and brown bodies lie scattered and often without any legal protection. During our site visits, local white hosts often referred to “the tragic events of 1838.” But all these land acknowledgements and vague ethnic cleansing acknowledgements only go so far. They have a clear stopping point. We found that stopping point. Landback is not included. Legal protection for one of the largest mass graves in the nation is not included. And even the ability to look for the graves is not included. They remain out there, somewhere beyond that arm wave, vulnerable to backhoes and excavators, at risk of being erased by a parking lot or a housing development.

Thank you for the well researched information in this article. Being from the Chattanooga area I learned in my research of the Trail of Tears, African Americans enslaved by the 5 tribes also made the gruesome travel to Oklahoma. Which begins the legacy of African American history in Oklahoma; Tulsa and Black Wallstreet, etc. I would imagine there were also a considerable amount of Black enslaved that were also held up in the same encampments among the mixed families you mentioned.

I bring this up to say these histories are so complex and intersectional.

Thank you for sharing your findings. There is so much we don’t know and many stories that have gone untold for far too long!

Thank you for reading it. Most of the information is now quite accessible thanks to some great interpretive panels and information at Ross’s Landing, Blythe Ferry, Red Clay, and the Hiwassee River Heritage Center. They’ve all worked with Cherokee Nation to produce some great displays. I highly recommend all of them.

The memorial walls at Blythe’s ferry list three numbers after some of the names (Cherokees/whites/slaves) who were with each family. Those names and that information comes from 1835 Henderson Rolls. You’ll see about 5% of the households had slaves – usually 1 to 5, but some had more than 10. These were the wealthiest Cherokees. There were also quite a few white fathers/husbands who removed with their families (though they didn’t have to). And several white missionaries removed with the Cherokees as well. I have ancestors in all of these categories.

Based on the Treaty of 1866, freed Black slaves of the Cherokees (called Freedmen) and their descendants are citizens of Cherokee Nation, regardless of “blood quantum.” Some of them were part of our group.

This is very interesting! I grew up 45 minutes east of the Eastern Cherokee Reservation. Our history books just mentioned the bare basics of the Removal and concentrated mostly on what the Eastern Cherokees had done. The Removal was mentioned as proof that the Eastern Cherokees were right to walk off up into the mountains. My family was removed to Oklahoma, but my white grandpa brought property in the Smokey Mountains and moved the family back in the early 1960s. This is the first time I’m learning most of the details in this article. . . my family always talked about the Removal being in 3 stages, so I’m guessing there were in the last batch to go. Wado for this information!

There was a great contingent from the Eastern Band of the Cherokees at this event. About 3,000 North Carolina Cherokees were rounded up and sent to Fort Butler in Murphy. From there, they were marched to Fort Cass and thus were part of the large encampment that I describe.

But many escaped the initial round-up. And some had private “reservations” in NC and were allowed to stay. They helped the escapees hide and survive.

I recommend checking out their information, as well this National Park Service brochure on the North Carolina Trail of Tears https://www.nps.gov/trte/planyourvisit/upload/North-Carolina-Trail-of-Tears-Brochure-508.pdf, and anything by Dr. Brett Riggs of Western Carolina Univ. He has researched this era extensively.

Good to know! I’ve never read any of the Park Service materials on it, just what we had in our NC textbooks. We did go to one of the “Unto These Hills” productions when I was 15, and my mom got so mad she nearly made us all leave. She said it was designed for white people. I’m glad we stayed, though, and the Oconoluftee Village put her more at ease. It was well worth the time to see both.

This 6-minute video by Cherokee Nation tells much of the same story: https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=534851141015392

Aloha from Hawaii, Stephen!

Can you tell me where you found the Cherokee Agency coffins receipt? I’ve never seen any hard fatality numbers for the emigration camps before. Quite a groundbreaking find!

My third great-uncle was Peter Hildebrand, a John Ross confidant and the detachment conductor mentioned on the large, blue historic marker at Blythe Ferry where you visited. His son Lewis W. personally delivered an anti-Removal petition to Chief Ross in Washington City on March 10, 1838 with 15,665 names on it, pretty close to the entire tribe at that time.

Peter’s niece Barbara Hildebrand (Longknife) Woodard crossed the plains to the California Gold Rush in 1850 before coming to Hawaii in 1865, and we’ve been here ever since. Unlike her uncle, the Longknifes were close friends with legendary Ross antagonist Stand Watie.

Thanks much, Glen.

‘Siyo, That receipt is on one of the display panels at the NPS Hiwassee River Heritage Center. See the big photo here: https://www.nps.gov/places/hiwassee-river-heritage-center.htm

It was for the administration of Fort Cass, which is were 12,000 or so Cherokees were eventually detained, waiting for the Tennessee River water levels to rise enough for crossing. Whooping cough went thru the camps, killing over a thousand children.